.png)

When Monetary Space is Spent Too Early

Markets are reacting less to fiscal arithmetic and more to a policy sequence that has left limited monetary room just as pressures build.

Gurumurthy, ex-central banker and a Wharton alum, managed the rupee and forex reserves, government debt and played a key role in drafting India's Financial Stability Reports.

February 4, 2026 at 5:18 AM IST

The market reaction to this year’s Budget has been widely read as a judgment on fiscal discipline, but that interpretation misses the more important macro signal. Bond yields have risen, the rupee has softened, and risk appetite has thinned, not because deficit numbers look alarming, but because policy sequencing has begun to look awkward.

The deeper issue lies at the intersection of fiscal ambition and monetary capacity.

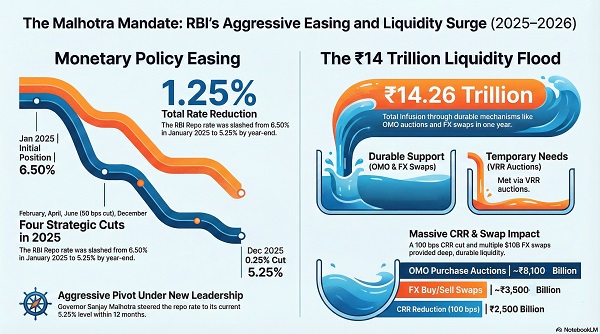

The Reserve Bank of India frontloaded monetary easing through rate cuts and liquidity injections during a phase when inflation had not collapsed, and financial conditions were not acutely restrictive, a choice that may have been preemptive but now carries consequences. That easing has reduced conventional policy headroom just as fiscal borrowing pressures intensify and market sentiment deteriorates.

Sequencing matters in macroeconomic management because monetary policy is most effective when deployed after fiscal stress becomes visible, not before it.

AI Generated

Today, bond yields are rising on supply concerns, the rupee is weakening amid portfolio outflows, and risk appetite is fragile, yet the central bank has already deployed much of its conventional ammunition. This does not constitute a failure of monetary policy, but it does point to a coordination problem, where fiscal and monetary authorities appear to have moved in opposite temporal directions.

If fiscal policy unsettles confidence while monetary policy lacks room to respond, the economy risks slipping into a negative feedback loop. Higher yields tighten financial conditions, weaker sentiment dampens investment, and the burden on monetary policy increases just as its capacity is most constrained. Markets, which price coherence as much as intent, are quick to recognise such dynamics.

Cycle, Sequencing

The policy challenge, therefore, is not about abandoning discipline or reversing consolidation. It is about recognising that timing and coordination are themselves instruments of macro management. When monetary space is expended early and fiscal pressures peak later, the economy is left exposed precisely when coherence is most needed.

Markets are not demanding dramatic intervention or policy adventurism. They are responding to the perception that the sequencing of policy tools has reduced flexibility at an inopportune moment, leaving fewer options available should conditions worsen. That perception, more than any single Budget number, explains the unease currently visible across asset classes.

Monetary policy does not operate in isolation, and its effectiveness depends as much on when it is used as on how aggressively it is deployed. When easing arrives before stress rather than in response to it, the risk is not excess accommodation but insufficient room when confidence finally frays.

This Budget will not be remembered for fiscal slippage. It may instead be recalled as the moment when markets began to question whether macro policy sequencing had kept pace with emerging pressures.

In macroeconomics, discipline without coordination can be as costly as indiscipline itself. When timing falters, even well-intentioned policy can lose traction in the eyes of markets.

Postscript: Announcing both the Budget and the MPC decision ((MPC meeting during February 4-6) just days before the release of new GDP and CPI series — the new series of GDP (base year 2022-23) will be released on February 27, 2026 and the new series of CPI (base year 2024) to be released on February 12, 2026 — is a little odd. Rebasing changes trend growth, output gaps, inflation persistence, real rates, and fiscal ratios — meaning policymakers are setting macro stance on metrics everyone already knows will soon be obsolete. A short deferral would have imposed negligible economic cost but materially improved coherence, transparency, and confidence.