.png)

The Rube Goldberg Machine of Progress: When Complexity Becomes Culture

From useless boxes to endless liquidity, we’ve turned simple problems into elaborate contraptions. But what if the machine itself is the point?

Phynix is a seasoned journalist who revels in playful, unconventional narration, blending quirky storytelling with measured, precise editing. Her work embodies a dual mastery of creative flair and steadfast rigor.

October 26, 2025 at 3:09 PM IST

Dear Insighter,

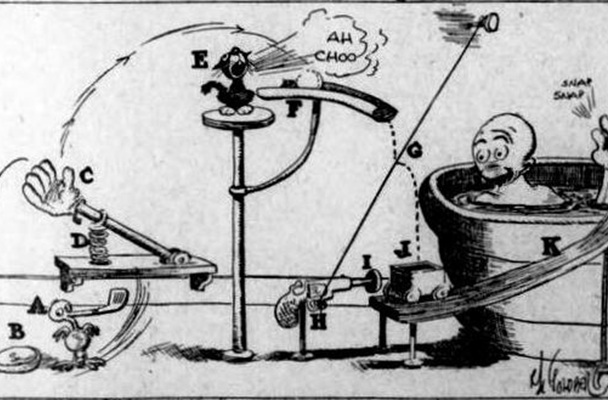

There’s something delightfully absurd about Rube Goldberg machines. You know the ones, those gloriously overcomplicated contraptions where a ball rolls down a ramp, hits a lever, releases a spring, and flips a switch, all to accomplish something as mundane as turning off a light. The “useless box” takes this to its logical extreme. Its sole purpose is to switch itself off. No productivity, no outcome. Just the joy of motion for its own sake.

And yet, watching these machines is pure delight. There’s something deeply human about unnecessary complexity—the urge to build something clever… just because we can. No wonder so many of our grand systems end up feeling like these designs.

Which brings us, inevitably, to global finance, our most intricate contraption of all.

R. Gurumurthy warns that the next financial crisis won’t look like the last one. There will be no singular collapse, no great bank run, no “Lehman moment.” Instead, it’ll emerge from the shadows—from the opaque rise of private credit, leveraged funds, and “techno-financial” mania that smells suspiciously like AI exuberance. Central banks have, for fifteen years, trained markets to expect rescue. Moral hazard has become muscle memory.

Global public and private debt now exceeds $300 trillion, or roughly 340% of world GDP. Debt has become both the lubricant and the anaesthetic of capitalism. Non-bank institutions now hold the bulk of global financial assets. They borrow, lend, and leverage like banks but without the guardrails of regulation or transparency.

We’ve built a machine so intricate that we’ve forgotten what it was designed to fix.

India, though, seems to be building its own contraptions with purpose.

Take the wave of foreign banks buying into Indian lenders. Emirates NBD’s move for RBL Bank and Sumitomo Mitsui’s investment in Yes Bank reflect a “buy, don’t build” logic. Gurumurthy calls it a sign of a maturing market: instead of reinventing the wheel, they’re acquiring ready-made modules to fit into a larger machine. But the true test lies in integration. Will these marriages of global capital and Indian platforms create real value or just temporarily align gears?

The Reserve Bank of India’s Expected Credit Loss framework is another gear being swapped in. The move to the Expected Credit Loss framework, as Babuji K explains, is a monumental shift from looking backward at losses to forecasting them forward. This isn’t mere accounting reform. It’s a cultural shift.

For decades, Indian banking prized collateral over credibility. The assumption was that assets, not intentions, determined trustworthiness. ECL flips that. It demands foresight: not “What does this borrower own?” but “What is this borrower’s future?” Rahul Ghosh calls it one of the most transformative changes since liberalisation because it forces banks to become lenders of trust, not just lenders of security.

That same trust quietly reshapes our fiscal philosophy. Nilanjan Banik points to a telling statistic: September’s GST collection hit ₹1.89 trillion, up from August’s ₹1.86 trillion, despite rate cuts. Lower taxes, higher compliance. Nearly 94% of India’s tax revenue now comes through voluntary compliance rather than raids or scrutiny. It’s a virtuous cycle: when citizens feel the system is fair, they participate more freely.

Barendra Kumar Bhoi notes that under the Taylor rule, India theoretically has up to 100 basis points of room to cut interest rates, given inflation near 2.5% and growth around 6.7%. Yet the RBI resists rushing in.

Arvind Mayaram argues that infrastructure financing must evolve beyond the old “Viability Gap Funding” model, where the government filled revenue shortfalls with cash grants. India’s future, he says, lies not in writing bigger cheques but building smarter ecosystems through structures that can sustain and finance themselves over time.

That design challenge is clearest in India’s power sector. Sharmila Chavaly warns that our centralised, one-way electrical grid—built for the industrial age—is buckling under twenty-first century demands. AI data centres, EV charging networks, and rooftop solar now push and pull power in multiple directions. Her vision of a decentralised “Arterial Grid” imagines a flexible, adaptive architecture that redistributes energy dynamically rather than dispatching it from a single hub. It’s a multi-part blueprint to replace a creaking model.

Meanwhile, Reliance Industries is quietly performing alchemy. As Krishnadevan V notes, Reliance consumes nearly 18 gigawatts of electricity across its operations. It’s more than the peak demand of some small nations. So it’s turning its own energy bill into a business model, generating renewable power to feed itself. It’s a perfect Rube Goldberg loop: complex, efficient, and entirely self-sustaining.

Every cog in India’s growth machine runs on commodities. Hemachandra Padhan observes that demand for copper, aluminium, and rare minerals is surging as India electrifies. Copper demand alone could quadruple by 2047. G. Chandrashekhar adds that the country’s next phase of growth will be fuelled by food, energy, metals, and fibre.

For two years, Indian refiners profited handsomely from discounted Russian crude. But that easy trade is fading fast. With new U.S. sanctions tightening around Rosneft and Lukoil, the cheap-crude window is closing, as observed in a BasisPoint Groupthink column. Margins are thinner, politics is louder, and the clever work-arounds that once kept the system humming are running out of road. The coming decade will show whether India can turn improvisation into lasting strategy.

Indra Chourasia warns that SEBI’s new settlement framework, intended for efficiency, risks eroding credibility if discretion overshadows deterrence. When enforcement looks negotiable, faith in the system falters.

In the digital realm, credibility faces its own test. Two years after its debut, India’s digital rupee is still searching for purpose. As Babuji K asks, what can it do that UPI or cash cannot? Innovation without utility is just motion without meaning.

And as we digitise, cybersecurity becomes the non-negotiable lock on the door. Shekhar Pawar estimates cybercrime could cost the world $10.5 trillion by 2025, with small and mid-sized firms bearing the brunt. In a hyperconnected system, the firewall is as critical as the fuel.

Even democracy runs on machinery. In Bihar, Amitabh Tiwari notes, the NDA is betting on experience while the RJD is betting on change, dropping nearly half its sitting MLAs to refresh its slate. But caste still defines the gears that turn electoral outcomes. Politics remains the most intricate system of all: one that mirrors, and magnifies, every other machine in society.

And then there’s advertising—the art of emotional engineering. Kirti Tarang Pande reflects on the late Piyush Pandey, whose 1990s Cadbury ad— the one with the dancing girl and the sixer—wasn’t about chocolate at all. It was about belonging. Pandey didn’t sell a product; he sold an identity. He built a sequence of cricket, music, and joy that turned a foreign sweet into an Indian emotion. The simplest mechanisms often achieve the most profound outcomes.

Are we making life too complicated? Possibly. But maybe that’s just the messy shape of progress—a conversation between precision and improvisation, between the neat plan and the happy accident.

A ‘useless machine’ isn’t pointless when it shows us how beautifully interdependent the world really is, how every lever relies on another to keep things moving. The ECL framework isn’t complexity for its own sake; it’s foresight. A decentralised grid isn’t overengineering; it’s resilience. A trust-based tax system isn’t naïve; it’s evolution.

The difference between a delightful folly and a world-changing invention lies in what the machine produces at the end. Does it turn off the lights… or power a nation?

As long as the gears keep turning with purpose, perhaps even the most complicated contraption is a kind of progress.

Until next time, questioning the contraptions we create.

Also Read:

- When Festival Sales Outsmart Our Better Judgement by Krishnadevan V: Festival sales tap psychology, not persuasion by using scarcity, credit, and choice overload to turn seasonal joy into a masterclass in impulse buying.

- Firecrackers as Class Aggression by T.K. Arun: The rich make competitive noise, pollute the air, switch on their purifiers and air-conditioners, and leave the less well-off to choke and sicken.

- The Annuity of Human Connections by Kalyani Srinath: In today’s economy of constant transactions, kindness remains our most undervalued asset.

- Money Can Buy Happiness — You’re Just Buying the Wrong Things by Kirti Tarang Pande: Money isn’t overrated, just misunderstood. The real question for the wealthy isn’t whether to pursue success, but what they choose to pursue with it.

- Ukraine and Russia: Is There Still a Road to Peace? by Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain: With Gaza calming and Europe tiring, the world’s attention may turn again to Ukraine, where fatigue, not force, could open a narrow window for peace.