.png)

Kirti Tarang Pande is a psychologist, researcher, and brand strategist specialising in the intersection of mental health, societal resilience, and organisational behaviour.

December 4, 2025 at 10:23 AM IST

A telecom safety app that had existed quietly in the background for months suddenly ignited a nationwide argument in India this week. Sanchar Saathi was trending on Twitter and not because of what it does, but because of what people feared it might do. In a matter of hours, the public mood transformed from curiosity to alarm.

Thousands of posts accused it of being intrusive, political voices jumped in, and Congress leader Pawan Khera went live calling it a “snoopy app.” And before the sentiment could settle, the government issued a hurried press release assuring the country that Sanchar Saathi will not be mandatorily pre-installed, therefore, it is not invasive, not surveillance, not anything remotely dangerous. The press note felt almost like someone trying to convince a friend that a firecracker isn’t going to explode after it sparks.

But the real story is not the app, it’s not even the government’s retreat. The real story is what the first forty-eight hours revealed about India’s psychology of digital autonomy. This was a behavioural moment, not a technological one. And once you read it through the lens of Kahneman’s System 1, the public reaction becomes not only understandable, but predictable.

When the government first signalled that Sanchar Saathi would be pre-installed on all new smartphones, something subtle but powerful shifted. A tool that had accumulated more than five million voluntary downloads without controversy suddenly felt like an intrusion. Nothing about the app changed; the default changed. In behavioural economics, defaults are never neutral. They are signals. They tell people something about who holds power in a decision, and who gets informed last.

Sanchar Saathi stopped feeling like a safety feature and started feeling like someone opening the door to your house without knocking. Even if they don’t enter, the act itself breaks the norm. Even if they say “you can lock it again,” your mind remembers that it was once opened without your permission. The government’s assurance that the app can be uninstalled, that the app takes no permissions, and that it cannot surveil you, was rational. But the reaction from people was never rooted in rationality. It was rooted in System 1—the fast, emotional, instinctive part of the mind that registers threats before they are explained.

System 1 does not read PIB press releases. It responds to meaning, not mechanics. And the meaning of pre-installation was unmistakable: something entered my device without my consent. That alone is enough to activate distrust. Because in this country, the smartphone is not just a gadget. It’s our digital shadow. It is our identity, our photos, our chats, our private universe. It is the one space we still believe we fully control. Any signal of default interference feels like a fingerprint on personal autonomy.

That is why the backlash spread faster than the government’s clarification. Fear is contagious; explanations are not. When citizens saw pre-installation, their minds jumped a predictable behavioural ladder: Why this? Why now? What next? What else can be pushed without consent? And once that “What else?” spiral begins, it does not respond to reasoning. It responds only to restored agency, which unfortunately cannot be restored retroactively.

The political reaction added another layer of emotional voltage. When Mr. Khera labelled the app “snoopy,” the metaphor worked not because it was accurate, but because it tapped into an old cultural fear, the fear of being watched. Surveillance is not only a technical threat; it is a psychological trigger. One word can activate decades of collective memory around control, overreach, and vulnerability. Once that frame set in, the government’s denial unintentionally amplified the story. Whenever institutions say, “We are not spying on you,” the public hears, “Spying was on the table.”

What made the situation more fragile was the speed of the government’s reversal. First the suggestion of pre-installation, then the minister’s “optional, you can uninstall,” and then a PIB note insisting the app does not even require permissions. In behavioural terms, this is policy whiplash. And policy whiplash deepens distrust, because people instinctively wonder why the state is clarifying so aggressively unless the initial instinct was correct. When a government must explain what an app cannot do, it legitimises the fear that it might have planned to.

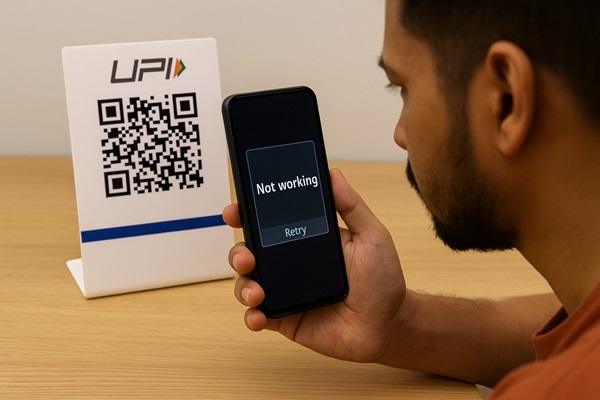

The irony is that Sanchar Saathi is not a villain. It addresses real threats: phishing scams, fraudulent SIMs, cloned IMEIs, lost phones. Most citizens would willingly adopt such a tool if it were introduced with clarity and consent. India has shown repeatedly that it embraces digital public infrastructure when it feels like a partner in the process. UPI, Aadhaar, DigiLocker, look at them, these worked because the psychological contract felt intact.

But this episode shows something deeper: India’s digital social contract is more delicate than policymakers assume. Trust is not a server. It cannot be patched after an emotional breach. Once people sense that defaults are shifting without their say, they activate their strongest behavioural reflex, which is protection of autonomy. The fear of losing agency is far more potent than the desire for safety. That is why people reacted more strongly to the installation method than to the app itself.

The government’s press release now tries to overwrite the narrative by placing blame on “misinformation” and reiterating voluntariness. But repairing trust cannot begin with telling people they overreacted. It begins with understanding why they reacted the way they did. And the answer is simple: autonomy is not a policy term. It is a psychological boundary. Cross it prematurely and people revolt, not because they object to security, but because security without consent feels like control.

The Sanchar Saathi episode is not a cautionary tale about technology. It is a lesson in behavioural sequencing. If you change a default before preparing the mind that must receive it, the mind doesn’t adapt—it resists. And it resists loudly, emotionally, politically, sometimes irrationally, but always predictably. The government is correct that the app is harmless. But it is also correct that citizens did not feel safe.

India is entering a phase where digital rights will be interpreted not in legal terms, but emotional ones. This is a democracy that now pushes back the moment consent feels assumed rather than granted. And this moment—messy, dramatic, instructive—marks the beginning of a new chapter in India’s digital governance: one where behavioural trust is the real infrastructure, and defaults are the real battleground.