.png)

By Tim Hirschel-Burns and Marina Zucker-Marques

Tim Hirschel-Burns and Marina Zucker-Marques are involved with the Global Economic Governance Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

October 10, 2025 at 5:33 AM IST

With developing countries facing intense financial pressure and developed countries slashing foreign aid, it can be tempting to dream of stumbling across a pot of gold. Dream no longer: The International Monetary Fund is currently sitting on 90.5 million ounces of the metal.

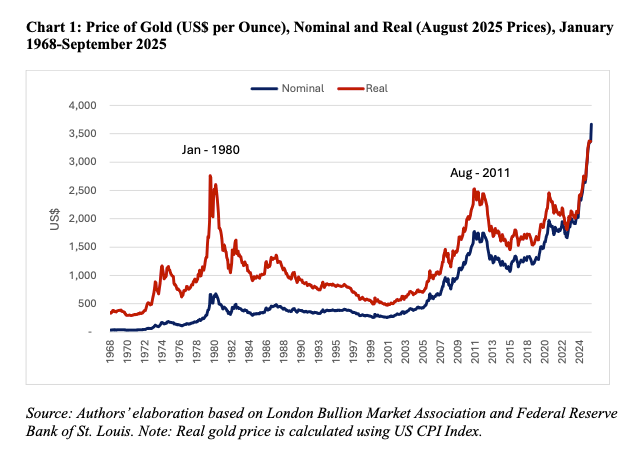

A relic of the gold standard, these holdings could be quickly turned into tangible funds. After hovering around $2,000 per ounce for most of the last half-decade, the price of gold has now topped $4,000 per ounce. Even in real terms, this is a record high, as Chart 1 shows. But you wouldn’t know it from looking at the IMF’s balance sheet, which values its gold at just $50 per ounce, a price last seen in the 1970s.

In reality, the IMF’s gold reserves are worth over $350 billion – more than Chile’s GDP. Selling just 10% of these holdings would generate enough funds to offset this year’s foreign-aid cuts.

Such a move is not without precedent. The IMF has sold gold several times, most recently in 2009-10. The Fund used the proceeds from that sale to create an endowment account that complements IMF revenue and subsidizes the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, its concessional lending arm for low-income countries.

The case for selling a small share of the IMF’s gold is even stronger today. The funds could help support cash-strapped developing countries, without requiring any donor contributions. And by placing them in an endowment account, the IMF could create a long-term, sustainable source of concessional financing for these countries. Perhaps most importantly, the Fund might never get a greater bang for the bullion.

The proceeds from a gold sale could be channeled into multiple existing trusts within the IMF. Perhaps the most promising candidate is the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), which covers repayments by vulnerable low-income countries of debt owed to the IMF in the aftermath of public health or natural disasters. Right now, just as these countries face large IMF repayments, the CCRT funds are nearly depleted, totaling around $115 million – barely enough to support one country in the wake of a crisis, let alone the dozens that could use it. With slight amendments to the CCRT’s eligibility criteria, the negative effects of aid cuts and trade adjustments on public-health financing could qualify as shocks meriting relief. This, coupled with a replenishment, would enable the CCRT to fulfill its potential.

Alternatively, these funds could be used to increase the concessionality of the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, scaling up support for low-income countries.

But regardless of which trust is selected, placing the proceeds from a gold sale in an endowment account would maximize their impact by continuously generating returns to be distributed to the trust. As an added benefit to the United States, the endowment fund could include investments in US Treasury bills, boosting demand for them.

This use of gold is entirely consistent with the IMF’s mandate. The aid cuts to some developing countries amount to several percentage points of GDP. The consequent need to increase domestic spending on public health, education, and related sectors will further strain governments that were already grappling with high debt-servicing costs. Moreover, reductions in aid and shifts in global trade have balance-of-payments implications, particularly in sectors that rely on imported goods, such as HIV/AIDS medications.

Selling some of the IMF’s gold also aligns with the stated desires of the US and other developed countries. Now confronted with high debt levels, challenging economic conditions, and the need to increase defense spending, these countries have stressed that the responsibility for funding global public goods must be more widely distributed, and that international institutions – including the IMF – should use their resources more efficiently. What is more inefficient than sitting on an idle pile of gold?

The unintended consequences that many fear, such as a slide in the price of gold, are unlikely to emerge. To avert this outcome in 2009-10, the IMF sold gold gradually, initially making off-market deals with central banks and coordinating with gold producers on market sales.

Nor would selling gold jeopardize the IMF’s financial stability. The Fund does not borrow on the market, so it does not need gold reserves to demonstrate its creditworthiness. Moreover, it has exceeded its precautionary-balances target of around $35 billion, a figure that does not count its gold reserves. Lastly, the vast majority of the IMF’s gold would remain untouched. If anything, these sales would strengthen the Fund’s financial stability by improving developing countries’ ability to repay their debts.

It is hard to imagine a more cost-effective solution to widespread foreign-aid cuts than the IMF selling a small share of its gold at no risk to its financial health and at no cost to its donors. That would be true even if the price of gold had not reached new heights. The fact that it has means that finance ministers and central bankers should act with a sense of urgency when they gather at the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank this month. There might never be a better time to dip into the Fund’s pot of gold.

© Project Syndicate 1995–2025