.png)

India’s Exchange Rate Regime Faces a Moment of Truth

With the rupee trading like a caged bird and IMF reclassification looming, India faces a reckoning on what its exchange rate regime really is.

Venkat Thiagarajan is a currency market veteran.

November 26, 2025 at 3:22 AM IST

*This story was filed before IMF reclassfied India's India’s Exchange-Rate Regime as “Crawl-like arrangement.”

The choice of an exchange rate regime is one of the most fundamental long-term policy decisions a country can take, and this has been evident ever since Polányi (1944) highlighted the historical significance of the gold standard in cementing a liberal economic order.

The theory is that, by fixing the parity of their currencies to an anchor currency, fiscally disciplined emerging economies could rapidly accumulate exchange reserves through export growth, maintain a high savings ratio, and provide certainty to investors. Such a policy environment would ideally lead to a low and stable domestic interest rate, thereby enabling the economy to retain the confidence of international investors.

However, every major international economic crisis, except Brazil's in 2002, has been rooted in rigid exchange rate regimes. Thus, Stanley Fischer noted in 2001 that “each of the major international capital market-related crises since 1994, Mexico in 1994, Thailand, Indonesia and Korea in 1997, Russia and Brazil in 1998, and Argentina and Turkey in 2000, involved a fixed or pegged exchange rate regime.”

Hence, many emerging markets have, over the past few decades, fully embraced flexible exchange rates alongside the rise of independent central banks and inflation targeting.

Words and Deeds

This fear has been evident in most emerging market countries, where nations that classify themselves as floating exchange rate regimes intervene quite vigorously over time. While many persuasive arguments have been offered for why countries intervene, the question remains why countries that intervene so actively continue to describe their regimes as floating. Thus, concurrently with fear of floating, there seems to be a “fear of declaring.”

One possible reason countries might fear declaring their true exchange rate policy is that international capital markets reward countries that are classified toward the flexible end of the spectrum. This creates an incentive to claim flexibility while practising management, reinforcing the persistent gap between stated intent and actual operations. Such behaviour helps explain why de jure flexibility often masks de facto control.

Regime Classification

Before 1998, the IMF had relied on countries’ officially declared exchange rate policies.

In 1998, the IMF introduced a system for independently assessing and classifying exchange rate regimes based on actual practices rather than official declarations.

The IMF’s classification system grouped regimes into categories such as hard pegs (currency boards, dollarisation), soft pegs (conventional pegs, crawling pegs, stabilised arrangements), and floating (managed float, free float).

The 2009 revision focused on greater precision and improved credibility. It gave markets a sharper lens for distinguishing between genuine floats and managed regimes, reducing the gap between official declarations and reality.

In addition to the Alesina and Wagner arguments that rely on institutional quality, there may be other reasons why markets prefer floating regimes. Hence, most countries are eager to be classified as floating-rate regimes.

Although floating regimes per se may not have appreciable advantages over other regimes, markets could have a strong subjective bias against fixed exchange rates. Such bias might stem partly from the fact that more recent international crises have generally erupted in countries with fixed exchange rates, or from the proliferation of inflation-targeting strategies, which presuppose that the exchange rate floats.

The “flexible” classification may signal to markets that the likelihood of an ill-advised defence of an unsustainable peg would be lower, and thus speculative attacks less likely.

The choice and practice of the exchange rate regime are vital to monetary policy, the central bank's primary responsibility. Yet, despite decades of debate on this subject, many unresolved issues remain. Indeed, it seems that no sooner has a conventional wisdom on exchange rates been established than a fresh wave of thinking emerges to challenge it.

India and IMF

Exchange rate cycles during this period were mainly driven by external factors such as commodity prices, US monetary policy, and the global financial cycle, as well as domestic dynamics, even as the RBI accumulated reserves whenever conditions permitted.

The exchange rate regime appears to have undergone a decisive shift following the adoption of the revised Economic Capital Framework at the RBI Central Board meeting on 26 August 2019. Notwithstanding the gyrations during the pandemic, the exchange rate was subsequently confined to a narrow band, with the central bank becoming the dominant participant.

Standard models of exchange rate determination identify two main channels through which intervention might influence the currency: the portfolio balance channel and the signalling channel. However, neither channel aligns with the empirical evidence, which shows that interventions sometimes work and sometimes do not. The only consistent message from the central bank over the past three decades has been its stock assertion that it does not target any particular exchange rate level and intervenes solely to contain volatility.

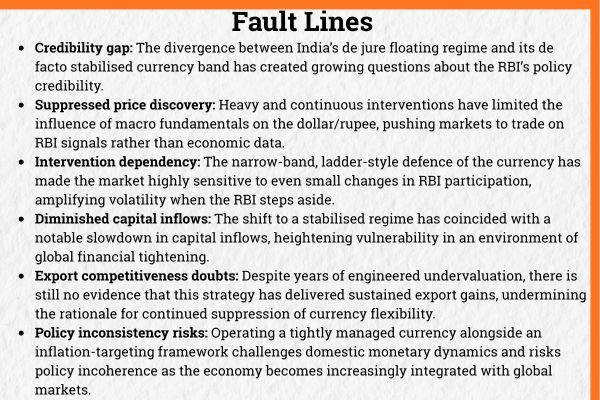

As an outcome, the policy agenda focused on sustained stability has turned out to be associated with a continuously depreciating currency and falling credibility of the central bank. While several studies have explored aspects of exchange rate dynamics, none has specifically examined the linkage between central bank credibility and exchange rate volatility. This credibility channel has therefore emerged as a critical but underexplored dimension of recent rupee behaviour.

The key, but far from straightforward, question is how much exchange rate movements matter for the real economy in this era of falling commodity prices. One may distinguish between effects transmitted through price competitiveness and those arising from market uncertainty.

It is common knowledge that the exchange rate is an endogenous variable, and its contribution to competitiveness or export growth may be difficult to disentangle. Indeed, there is still no evidence that engineering a persistent undervaluation over the past five years has materially supported export growth.

As the time-tested macro forces were not allowed to influence exchange rate determination, markets have increasingly watched for subtle signals from RBI’s intervention strategies and positioned themselves accordingly. This has magnified the signalling effect of even marginal shifts in RBI’s market presence.

The coexistence of a caged bird exchange rate system, operating almost like a fixed exchange rate regime, alongside an inflation target has long been regarded as a challenge for domestic monetary dynamics, with the potential to trigger volatility in price levels on either side of the spectrum.

The IMF recognised this shift in its staff report dated 27 February 2025, noting that while India’s de jure exchange rate arrangement remained “floating”, its de facto arrangement had been classified as “stabilised” for the period from December 2022 to November 2024.

Classification as a stabilised arrangement entails a spot exchange rate that stays within a 2% margin for six months or more, subject to a limited number of outliers or step adjustments. This classification requires that the statistical criteria are met and that the exchange rate remains stable because of official action, including structural rigidities in the market.

Impact of Intervention

The RBI bulletin for September 2025 shows purchases of $2.2 billion and sales of $10.11 billion, while bringing down the forward short position by $6.05 billion.

Recently, the dollar/rupee was defended at 88.80 on the upside for more than two months, and the RBI surprisingly stepped away from the offer last Friday, sparking panic and uncertainty in the markets.

A good example of what can happen when a central bank scraps its long-held peg is the Swiss National Bank's removal of its peg to the euro at 1.2000 Swiss francs per euro in January 2015. This announcement sent the Swiss franc about 30% higher in the immediate aftermath.

However, the breakaway up move in the dollar/rupee did not extend beyond 89.60 in the offshore segment and eased off to 89.00 within two trading sessions. The consensus is that the next step in the ladder between 89.00 and 89.50 has been opened up for now.

As usual, there has been no communication from the authorities, and the markets have been abuzz with speculation on their sudden withdrawal from defending the key level of 88.80. Simply put, all the exporters and importers have been staying awestruck as of now.

The street is talking about the IMF staff report, which will be released in the next few days and could reclassify the dollar/rupee to a crawling peg arrangement. Classification as a crawling peg involves confirming the country's authorities’ de jure exchange rate arrangement. The currency is adjusted in small amounts at a fixed rate. The rules and parameters of the arrangement are public.

So, it is presumed that the RBI had to step aside from 88.80 to win the IMF's confidence and convince them to keep the current classification of “stabilised”. This interpretation may not be definitive, but it has gained traction in the absence of communication.

There is always an undeniable interplay between exchange rates and capital flows in an environment of increasing capital market integration. Indeed, there has been a long-standing view that an emerging economy under a peg, with government budget imbalances, trade deficits, and free-market policies that facilitate capital outflows, is likely to become vulnerable to sudden stops in capital inflows.

It might be seen as coincidental that capital inflows had dramatically diminished in intensity since February 2025, following the classification of the exchange rate regime as stabilised. If the apprehensions of re-classification into crawling pegs turn out to be true, there is indeed a key risk that could lead to further negative impact on capital inflows.

Finally, currency regimes determine the stochastic distribution of the fundamentals and the effect of the market fundamentals on the macroeconomic performance. This is because the credibility and effectiveness of macroeconomic policies depend on the currency regimes. Thus, a currency regime exerts not only a direct effect on growth through its effect on the market fundamentals, but it also has an indirect effect on growth.

As such, policymakers should take cognisance of the fact that the choice and practice of the country's exchange rate regime should be synchronous and should not be lost in the pursuit of ideal, elusive goals of stability and the arrest of volatility.

It would be prudent to let the bird fly in both directions and breathe fresh air.

Also Read:

From Controlled Calm To Market Chaos, RBI’s Stability Bet For Rupee Unpegged