.png)

The Broken Compass Of Indian Insurance: Where Is The Consumer?

Despite its central role in financial protection, India’s insurance sector often appears to place industry functionality ahead of consumer trust—reflecting a regulatory framework that has yet to fully embrace urgency and consumer-centricity.

Dr. Srinath Sridharan is a Corporate Advisor & Independent Director on Corporate Boards. He is the author of ‘Family and Dhanda’.

June 11, 2025 at 6:57 AM IST

Long before the modern insurance industry took shape, the idea of risk-sharing and collective protection had deep roots in Indian society. Traditional Indian communities practised forms of mutual aid and collective responsibility—be it village-level grain banks, caste-based welfare pools, or religious endowments used to support families during illness or death. These indigenous risk-mitigation mechanisms were informal, trust-based, and socially embedded. They may not have carried actuarial sophistication, but they carried moral clarity. Protection was seen as a collective ethic, not a product to be sold.

Colonial Hangover

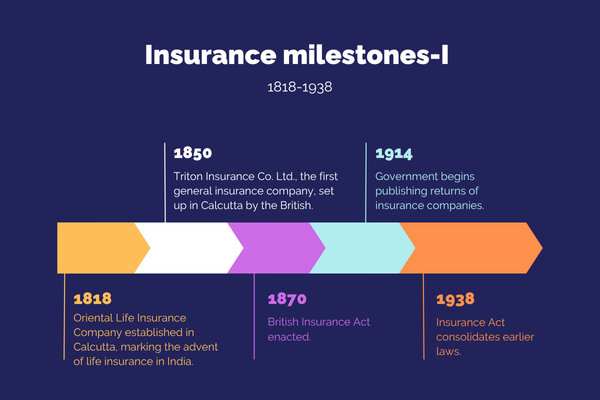

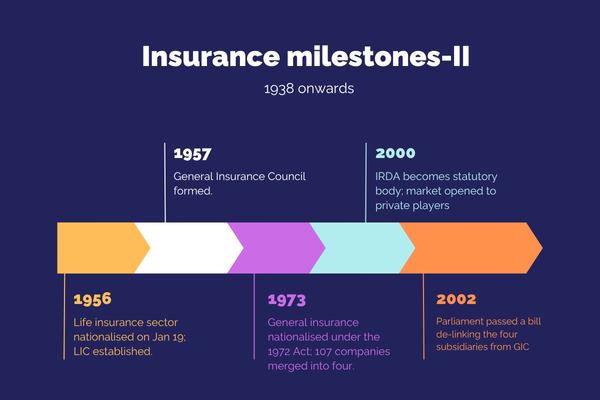

The colonial period introduced new ideas of insurance, largely to safeguard the interests of the empire and its mercantile ventures. Over time, this gave rise to a nascent domestic insurance sector, which gained scale during the post-Independence period through nationalisation. Life Insurance Corporation, established in 1956, and later the General Insurance Corporation, became synonymous with state-backed financial security. For decades, these institutions occupied near-monopolistic roles, offering basic protection with a public-service ethos, albeit with limited consumer choice or competition.

The formal opening up of the insurance market came in 1999, when the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority was established through an Act of Parliament. The idea was to liberalise the sector, invite private and foreign capital, increase penetration, and create a robust regulatory framework to ensure fair play. IRDA’s formation was a landmark moment—marking a shift from a state-monopoly model to a market-driven one, with the regulator expected to play the role of neutral arbiter and consumer protector.

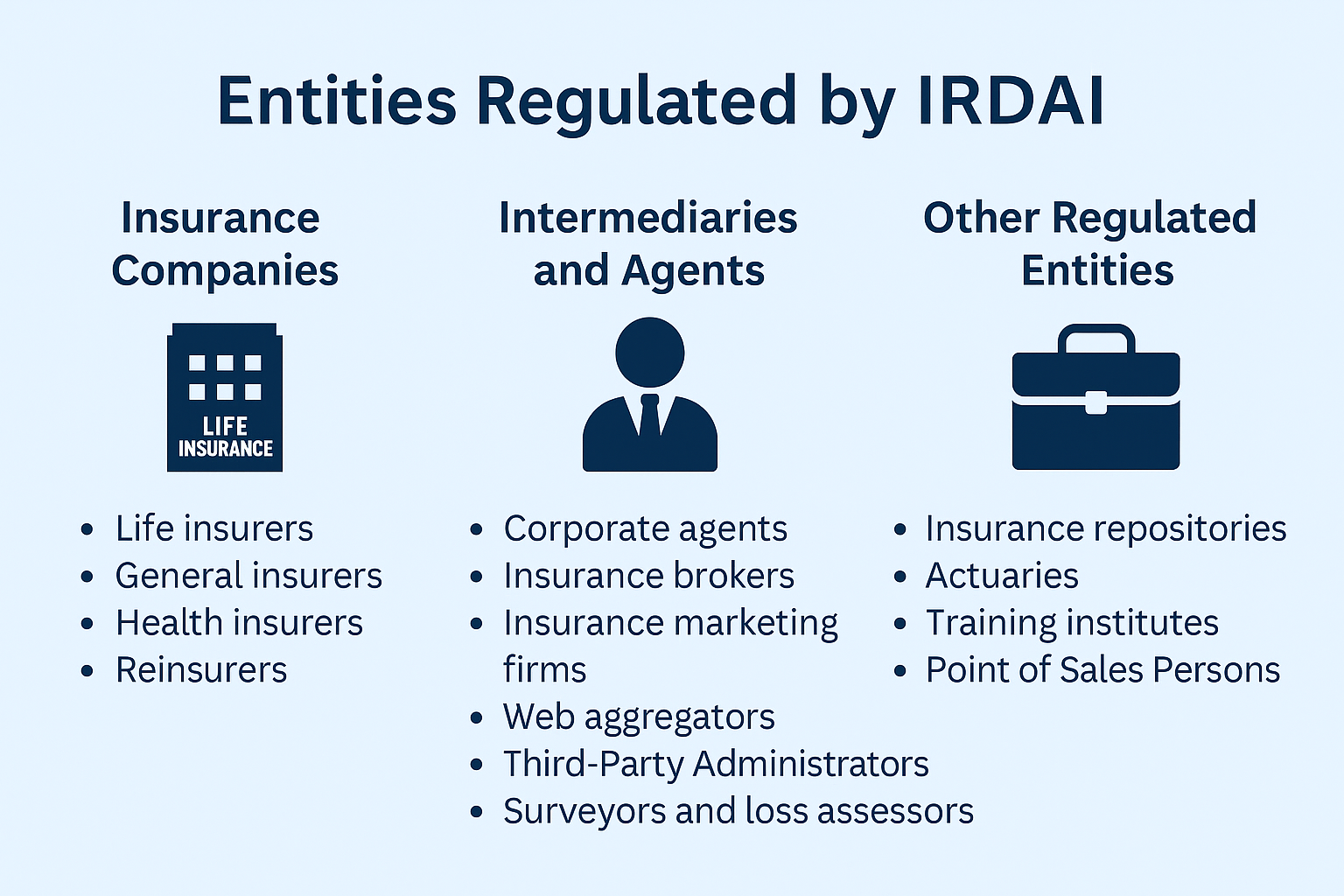

In the twenty-five years since its creation, IRDA—renamed IRDAI after becoming a statutory authority—has overseen the expansion of the insurance market in both life and non-life segments. Private players have entered, digital distribution has scaled, and the language of competition has become routine. Yet beneath this growth narrative lies a more troubling story. Penetration remains low by global standards, public confidence remains shaky, and consumer redress remains uneven. The regulatory posture has often been reactive, procedural, and weighted toward industry facilitation rather than consumer empowerment. The promises of liberalisation have not translated into a consumer-first architecture. What was meant to be a more vibrant, competitive, and fair system has instead become more opaque and structurally tilted against those it claims to serve.

One of the most pressing trust challenges in India’s financial landscape may lie in the insurance sector—not necessarily in its products or penetration levels, but in the limited rigour of regulatory supervision that has yet to place the consumer at its core. The central issue is not market inefficiency or fraud, but the absence of a genuinely consumer-centric regulatory approach. Unless IRDAI undergoes organisational redesign and a shift toward a more assertive, independent, and conduct-focused posture, the sector risks continuing with a credibility gap that undermines public confidence.

Buyer Beware

Insurance, by its very nature, rests on a foundational relationship of trust. Consumers pay today for a promise tomorrow, often at life’s most vulnerable moments. Yet, recent surveys and everyday experiences reveal a stark reality: a significant number of policyholders would not recommend their insurer to a friend. That alone is a deeply worrying indicator in a sector where customer advocacy should be organic. The public perception that insurers operate for themselves, rather than for their policyholders, is not just anecdotal anymore—it is becoming institutionalised.

In Indian insurance, premiums are processed swiftly, but claims often face layers of suspicion, paperwork, and delay—undermining consumer confidence in the very moments protection is needed. Despite growing public awareness about misaligned incentives, value chain corruption, and widespread consumer neglect, the insurance regulator has yet to demonstrate the institutional resolve needed to initiate deeper course corrections. It is not that reforms have been absent. Regulatory change has occurred, but it has been incremental and often cosmetic. The broader posture of IRDAI has been one of accommodation rather than assertion. While other financial regulators have demonstrated stronger enforcement and oversight capabilities, IRDAI seems to have been caught in a culture of caution. The sector’s most pressing reforms—those that truly prioritise consumer welfare—remain timidly addressed or are simply absent.

The Opacity

One of the gravest gaps in India’s insurance regulatory landscape is the near-total absence of public-facing accountability. IRDAI’s public disclosures remain limited compared to international best practices in regulatory transparency. There is no routine publication of audit findings, no granular breakdown of complaint redress effectiveness, and no mechanism for consumers to see how their grievances inform regulatory decisions. The absence of a real-time enforcement dashboard, public blacklisting of malpracticing agents or intermediaries, or performance scorecards for insurers leaves citizens in the dark—and makes the regulator unaccountable to the very people it claims to protect. A truly modern regulatory institution must subject itself to public scrutiny, not just industry lobbying.

The Indian insurance industry has become a closed loop of insiders—experienced executives moving between firms, perpetuating the same set of operational assumptions. Growth is measured in premium volumes, market share and solvency margins, rarely in terms of claim settlement ratios or customer satisfaction. Talent circulates, but rarely does new thinking emerge on making insurance truly consumer-centric. The result is an industry that feels like it is designed for itself, not for the people it was meant to protect.

Nowhere is this disconnect more evident than in the claims process. Fraud prevention is, of course, essential, but the dominant mindset is adversarial—built around distrust rather than service. Honest claimants are treated with suspicion, forced to furnish endless documentation, explain their circumstances repeatedly, and then wait for weeks or even months for a response. Each claim becomes a trial. This approach may reduce fraudulent payouts in the short term, but it does so by punishing the very people the system is supposed to support. It breeds hostility, not assurance. Even in general insurance, concerns about low settlement values and delayed processing are commonplace. No amount of digital infrastructure or AI-led automation will fix this if the prevailing institutional attitude remains one of mistrust.

Gaming The System

In parallel, the regulatory tolerance of deeply embedded practices—like the mis-selling of bundled products, inflated hospital bills in collusion with providers, and lack of standardisation in exclusions—continues unabated. Health insurance, in particular, has become emblematic of the sector’s dysfunction. The inflation of hospital bills is now an open secret, yet the regulator’s silence on this matter is striking. It is not just a pricing issue—it is a credibility issue. When insurers use the excuse of fraud to deny full settlements, and regulators do not push back, trust erodes further. A shift in regulatory philosophy is long overdue. One meaningful reform would be to mandate full and prompt settlement within a defined window, with the onus on insurers to prove exceptions rather than the burden remaining on consumers to fight for their rightful dues.

And then there is the matter of insurance penetration, often cited as a policy concern. India’s insurance penetration stands at just 4.2%, heavily skewed toward life insurance, which comprises 76% of total premiums, compared to a global average where non-life dominates at 56.3%. Despite this, much of the industry conversation remains fixated on market expansion, digital reach, and foreign capital. While important, these are secondary to the core crisis—trust. The obsession with distribution scale and industry growth drivers is misplaced if consumers cannot feel secure in the protection they’ve paid for.

Peer Practice

Meanwhile, regulators such as the Reserve Bank of India and SEBI have demonstrated stronger action when faced with industry failures or consumer risks. Both RBI and SEBI have evolved supervisory frameworks that adapt to changing market realities—often combining enforcement with clarity of purpose. IRDAI, by contrast, has remained procedurally conservative and structurally underpowered, particularly in relation to market conduct supervision The insurance regulator, however, has yet to show that level of institutional resolve. Even the framework around bancassurance and commission structures has invited concern, with documented cases of insurers employing unregistered or third-party intermediaries, masking illegal commissions through fake invoicing. No wonder industry might be one of highest users of travel agencies and event agencies for its R&R outings. Rather than being isolated episodes, these examples suggest the existence of a broader, permissive culture—one in which bending rules is normalised and consequences are infrequent. This is not just a regulatory oversight; it is a structural failing.

Unlike their global counterparts in markets such as the United Kingdom, Australia or Singapore, IRDAI has yet to adopt a robust conduct-based supervision framework. Regulators elsewhere run mystery audits, enforce fair treatment of customers as a statutory principle, and publicly sanction firms that deviate from fiduciary norms. In contrast, India’s insurance regulation appears tentative, sometimes deferential, and far too consultative for a sector where power asymmetries are vast and stakes are life-altering. In the absence of assertive public enforcement, even well-meaning regulations lose their credibility.

India is in the midst of a profound demographic transition. With a median age of under 30, a burgeoning urban middle class, and increasing formalisation of the workforce, millions of first-generation financial consumers are entering the insurance ecosystem. These are citizens with rising aspirations but limited institutional memory of navigating complex financial products. Unlike earlier generations who relied on state-backed insurers or employer-led benefits, today’s consumers are expected to make independent, often digital-first, decisions about life, health, and asset protection. This shift demands a regulatory regime that does not just assume consumer literacy, but actively compensates for its absence through stronger safeguards, simplified disclosures, and easier grievance mechanisms.

Trust Issues

The demographic dividend, if not matched by regulatory foresight, can quickly become a consumer debt. Younger policyholders, unlike their predecessors, are not content to passively accept denial of claims, mis-selling, or opaque processes. They demand transparency, speed, and fairness. Without recalibrating the insurance regulatory framework to reflect this expectation—through conduct-focused supervision, digital accountability, and outcome-based oversight—the trust gap will only widen. A regulatory approach that remains primarily aligned with the supply side of the market may struggle to stay responsive and effective in a future shaped by increasingly empowered, demand-driven demographics. The need is not just for more products or players, but for a regulatory culture that understands the modern Indian consumer as a rights-bearing stakeholder, not a passive recipient.

If left unaddressed, consumer distrust of the insurance sector could produce consequences far beyond poor satisfaction metrics. It risks converting a generation of potential policyholders into lifelong sceptics. This has deep implications for household financial resilience, public health costs, and even systemic stability. When consumers believe that insurance will not support them in crisis, they disengage altogether—either by underinsuring, delaying participation, or treating premiums as sunk costs rather than security instruments. The consequence is not just a reputational deficit for insurers, but a widening of socioeconomic vulnerability at scale.

Equally concerning is the persistent stagnation in insurance penetration. Despite decades of liberalisation, India’s insurance landscape remains underdeveloped in both breadth and depth. This is not simply a function of awareness or affordability. It is a byproduct of a regulatory system that has failed to nurture trust as a policy outcome. Low penetration is not merely a market inefficiency—it is a governance signal. If large segments of the population remain uninsured, the state will ultimately bear the fiscal and social burden of unprotected risk. In this light, regulatory reform is not a sectoral preference, but a public policy necessity. The future of India’s risk architecture depends on whether the insurance sector can become truly inclusive, equitable, and accountable.

The Industry Tilt

A deeper concern is the perceived proximity between the regulator and the industry it oversees, which may dilute consumer-centric outcomes. Advisory committees are disproportionately populated by industry participants. Public consultations are often limited in scope or perceived as mere formality. The absence of independent consumer protection units within the regulatory architecture reflects a troubling alignment of institutional focus toward industry convenience over public interest. When a regulator begins to see the sector’s commercial success as its own performance metric, the consumer becomes incidental. These suggest an institutional design tilted toward industry continuity over consumer challenge. This is a question of governance asymmetry.

What is needed now is not another set of incremental circulars or pilot projects, but a decisive shift in regulatory posture. It is time for IRDAI to reassert its role as a steward of public trust, not as a facilitator of industry convenience. That means stronger surveillance, greater enforcement powers, consumer-first design of redress mechanisms, and the political will to confront entrenched interests. It also requires convergence across regulators to address issues like mis-selling and fragmented accountability. Consumers don’t care whether they were mis-sold by a bank, an insurer, or a fintech—they just want justice. And justice today is elusive.

Even today, ask any experienced insurance lawyer about the Indian insurance ecosystem, and you’ll hear a consistent refrain: the system often places the onus on consumers to prove their claims, reflecting a culture that errs on the side of institutional scepticism. This adversarial posture runs so deep that even ostensibly positive sectoral statistics, like claims settlement ratios, are met with skepticism. Much of the public’s distrust stems not from isolated incidents, but from lived experience with a system that presumes bad faith rather than good.

Ultimately, one cannot reform insurance through digital platforms and clever marketing alone. What is at stake is not just the efficiency of the industry but the moral legitimacy of its social contract. Insurers exist because consumers believe that their claims will be honoured and their dignity respected in moments of distress. If that belief is broken, the sector becomes hollow. A regulatory spine is not a matter of personality—it is the outcome of institutional design.

Tick The Box

Fundamentally, there is a deficit of vision—a failure to define what a just and efficient insurance market should look like over the long term. A forward-looking regulator would not only enforce compliance but shape market norms: embedding transparency, standardising customer disclosures, mandating fiduciary duty among agents, and using data to correct systemic imbalances.

There is no publicly articulated conduct agenda, no institutional benchmarking against global best practices, and no strategic commitment to restoring public trust as a core regulatory outcome. This vacuum of vision makes IRDAI not just a passive regulator, but a participant in the very trust deficit it ought to resolve. Until IRDAI builds a philosophy that puts ethical outcomes above administrative process, Indian insurance will remain a rule-bound system with no soul.

In a sector deeply influenced by human behaviour, IRDAI has yet to embrace behavioural economics or systemic risk modelling in its supervisory design. Consumers don’t always act rationally—especially under financial stress—yet policies are drafted as if they do. There is little effort to study claim drop-offs, track long-term consumer sentiment, or understand why grievance mechanisms fail. Without investing in behavioural insights and systems thinking, regulation remains blind to how real-world failures accumulate—not just from bad actors, but from friction, opacity, and fatigue. A conduct regulator that ignores behavioural data will always miss the root causes of consumer harm.

Regulators Matter

If we aspire to build Viksit Bharat—a truly developed nation—we must begin by trusting our own people. A regulatory system that treats citizens as suspects rather than stakeholders undermines not just sectors like insurance, but the very social contract on which economic progress rests. Developed nations are not defined by GDP alone, but by regulators who exist first and foremost for the public good.

A regulator without a clearly articulated consumer philosophy may issue volumes of circulars yet miss the opportunity to restore public trust. In a sector built on asymmetry and delayed fulfilment, regulation must be more than administrative—it must be anticipatory and just. Its true strength lies not in preserving industry convenience but in unsettling it when consumer interest is no longer central. Regulatory maturity is measured not by control but by courage—the courage to realign power where it rightfully belongs: with the people who place their faith in the system long before they ever make a claim.

For a regulatory system that wants to achieve 100% insurance access and coverage to every Indian by 2047, the task ahead of it is not just external to its offices, but to start from within. A culture of consumer-trust, regularity-rigour, understanding of changing Indian demographic shifts and financial needs and wants, and an independent, transparent and agile-regulatory-supervision.

Most insurance contracts include clauses for an “Act of God”—a rare, external event beyond human control. But should it really take such an event for India’s insurance regulator to become truly consumer-centric? Or will we wait for a crisis before we remember who this sector was meant to serve in the first place?