.png)

Dr. Srinath Sridharan is a Corporate Advisor & Independent Director on Corporate Boards. He is the author of ‘Family and Dhanda’.

May 21, 2025 at 8:18 AM IST

While India has demonstrated pockets of excellence in manufacturing—pharmaceuticals, automotive components, and select capital goods, amongst others—the broader truth is harder to ignore. The capacity to scale with precision, consistency, and global quality at low unit economics across industrial sectors has not been India’s defining strength. This is not a dismissal of what has been achieved, but a sober recognition of what it takes to lead in the emerging manufacturing order.

India must confront a fundamental question: What does it truly want to be good at in the global manufacturing landscape? Once that question is answered, the policy focus must shift from horizontal incentives to vertical depth. Much of India’s recent industrial activity has been driven by fiscal incentives and FDI flows, resulting in scale without sovereignty. What the country now needs is depth—depth in design, materials, component ecosystems, and systems engineering.

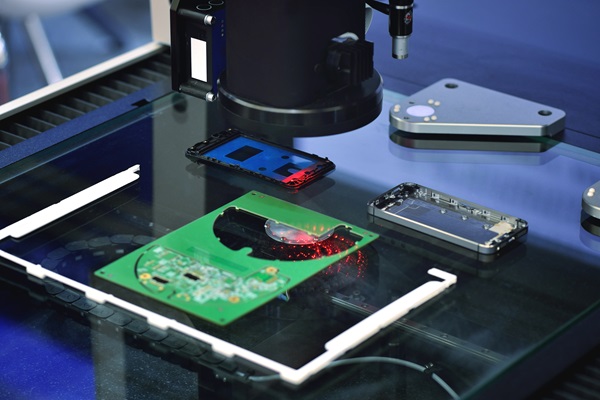

The numbers are instructive. Each Apple iPhone, with a retail value of around $1,000, is a composite of global specialisation. The United States captures roughly $450 through design, software, and branding. Taiwan earns $150 from chip fabrication. South Korea, through its display and memory components, takes home about $90. Japan contributes $85 via optics. Even countries like Vietnam and Germany earn meaningful value through specialised inputs.

In contrast, China and India collectively capture less than $30 per unit, or under 3% of the total value. For India, this figure is largely subsidised by the state under the Production Linked Incentive scheme. And as New Delhi slashes tariffs on components to appease global OEMs, its own domestic component ecosystem will have to pick up speed. Does it mean that we, in effect, are paying to be included in a value chain we don’t control?

Paradoxically, that disruption may be the push India needs. A hard reset could compel the country to invest in meaningful areas—batteries, chip packaging, embedded systems, precision tooling, and displays. It could free up policy bandwidth from assembly economics and redirect it towards component sovereignty. Such a shift would also demand long-overdue introspection about what real industrial development entails.

India’s experience with technology services holds a cautionary tale. The rise of companies like Infosys, TCS, Wipro, and Cognizant created jobs by the millions. Yet they did so through back-end services, legacy software maintenance, and outsourced support. India never built equivalents of Accenture Strategy, McKinsey, or Palantir.

The intellectual capital existed, but the strategic architecture to convert it into deep-tech or knowledge consultancies did not. What emerged instead was a tiered workforce of highly capable engineers in low-leverage roles - cyber-coolies in the digital age. This is not a critique of individual effort, but of systemic underreach. We often celebrate exports and employment without nurturing intellectual property or strategic control. The same misstep must not be repeated in manufacturing.

The PLI scheme is a useful instrument, but it cannot be mistaken for a manufacturing strategy. Fiscal incentives are tactical tools. They do not build institutional depth. India must invest upstream—in cleanroom infrastructure, testing and measurement systems, advanced materials R&D, and systems integration capabilities. Without this substrate, India will remain a destination for screwdriver technology—fragile, shallow, and replaceable.

Meanwhile, the ground beneath traditional manufacturing is shifting. Disruptive technologies such as AI, IoT, and advanced automation are redefining industrial competitiveness. Human interface in factories is declining. Smart manufacturing will be capital-intensive, software-defined, and precision-driven. The countries that win will be those with advanced engineering capacity, integrated STEM ecosystems, and the ability to embed intelligence in machines, not just operate them.

This also calls for a clearer reckoning by the political system and policy establishment. The new age of industrial policy cannot rely on legacy assumptions that job creation will naturally follow capital deployment. The very technologies that promise industrial competitiveness—automation, robotics, machine learning—also reduce the demand for human labour. Offering land and tax breaks to attract manufacturing investment may no longer translate into large-scale employment. The notion that industrialisation is the default path to labour absorption must be re-examined. India will need new models of economic inclusion that go beyond the factory floor.

This brings India to a point where it has to decide newer ways of dealing with its demographic shifts. A nation cannot leap into deep-tech manufacturing with a shallow STEM pipeline. India’s engineering output may be voluminous, but its quality is patchy. According to World Bank data, India’s manufacturing value added per worker is under $8,000. China’s is over $25,000. In South Korea, the figure exceeds $100,000. These are reflections of India’s gaps in vocational training, applied engineering, process design, and capital intensity.

Narratives alone will not bridge this divide. India needs a national engineering doctrine that re-establishes rigour in technical education, funds industrial research with seriousness, and celebrates design thinking and systems-level innovation. It needs to return engineering to its role as a nation-building pursuit, not merely a credential to export.

The broader strategic context makes this transition urgent. Manufacturing is no longer just an economic function. It is geopolitical. In an era of technology sanctions, semiconductor nationalism, and splintering trade blocs, control over industrial value chains is power. The ability to make, scale, and own critical technologies determines whether a country is a rule-maker or a rule-taker.

India cannot afford to outsource its future or rent relevance in the global order. If it remains at the periphery of value chains, it will remain vulnerable to supply disruptions, IP lock-ins, and policy blackmail. A low-cost workforce is not enough. A deep industrial state is now a prerequisite for sovereignty.

India does not lack ambition. It lacks alignment. It does not lack talent. It lacks institutional seriousness. It does not lack opportunity. It lacks clarity about what it must stop doing in order to do what truly matters.