.png)

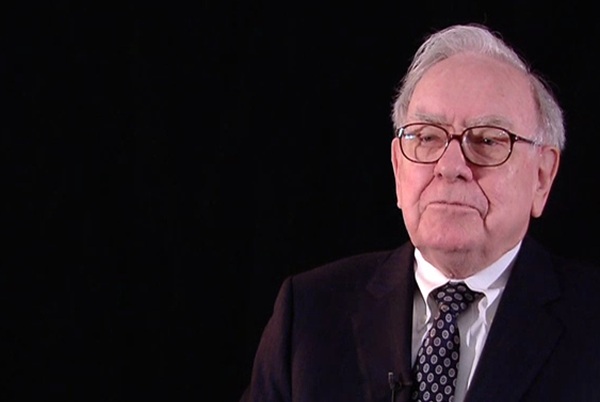

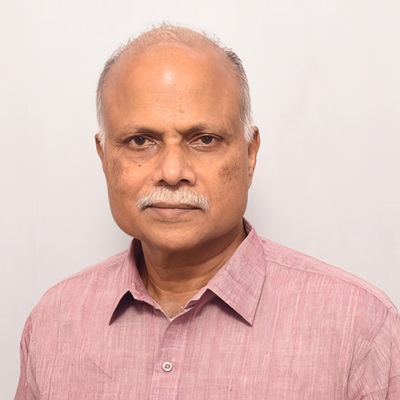

T.K. Arun, ex-Economic Times editor, is a columnist known for incisive analysis of economic and policy matters.

November 12, 2025 at 4:08 PM IST

A ruling by the Swiss Federal Administrative Court on October 14, holding as illegal the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority’s decision to write down Credit Suisse’s Additional Tier 1 bonds, as part of the state-directed merger of troubled Credit Suisse into rival banking giant UBS, has revived hopes in India for those pursuing a case in the Supreme Court against the similar writing down of AT1 bonds issued by Yes Bank, as part of its salvage operation. Their optimism is misplaced.

Both FINMA and UBS are challenging the ruling by the Federal Administrative Court.

Why should the Indian public at large be concerned about the fate of how an arcane bit of financial regulation is exercised? Should the broader public limit their concern over banking to the interest rates banks charge on loans and offer on deposits, the consumer experience and vigilance against financial scamsters?

The public at large are stakeholders in the Yes Bank AT1 verdict because it would decide how much of taxpayer money would go into bailing out the next bank that fails. If the Supreme Court fails to uphold the writing down of the AT1 bonds the administrator undertook with the backing of the banking regulator, RBI, while salvaging Yes Bank, the entire purpose of creating a loss-absorbing capital buffer in addition to equity would be defeated and taxpayers would be left to carry the cost of future bank bailouts, along possibly with depositors.

AT1 bonds are relatively recent instruments. They were thought up by the Bank for International Settlements as part of the Basel III norms, tighter regulation that was deemed necessary in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09, in which governments had to bail out several banks in different parts of the world.

The normal purpose of equity is to the absorb the impact of a corporate collapse and protect other providers of capital in the form of debt. Lenders, suppliers who have provided goods and services on a deferred payment basis but have not been paid, bond holders, and similar other creditors are entitled to the proceeds of selling off a failed firm and its assets, before equity holders can recover a single rupee from the funds generated from liquidation. If there are funds left over after meeting the claims of creditors, equity holders can get some of their capital back.

In the case of large banks, failure of one entity could lead to failure and distress across the financial sector, because of diverse and multiple interlinkages between financial institutions. Therefore, governments step in to bail out collapsing banks, with far greater readiness than they show for bailing out failed companies.

Yet, during the financial crisis, Republican president Geroge Bush and his successor, Democrat Barack Obama, both used public funds to bail out banks and large companies like General Motors, whose vast vendor networks would also have collapsed if the company had gone under.

Banks had to be rescued by governments across Europe and Britain, using public funds, including borrowed funds, and, in some cases, the deposits of unfortunate souls who had chosen these failed banks to hold their savings.

It was to prevent having to divert public funds to bail out privately mismanaged banks that the Basel III norms of capital adequacy were devised. These devised a layer of capital that would absorb loss while the bank is yet a going concern, in addition to equity. Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1), is the first layer of loss absorbing capital. An additional Tier 1 layer of capital, designed to absorb loss while the bank is still a going concern and has not been liquidated, holds a special category of bonds. These AT1 bonds can stop paying coupon (the promised interest) or even be written off in part or full, to prevent commandeering the funds of depositors or of the government to prevent liquidation.

Tier 2 capital consists of bonds that come into play on a gone-concern basis, before depositors and regular bond-holders are touched.

Basel III norms of capital adequacy stipulate CET1 should be greater than 4.5% of risk-weighted assets, Tier 1 capital (common equity and AT1 bonds) greater than 6%, and that Tier 1 and Tier 2 combined should be greater than 8% of risk-weighted assets. For banks that are deemed systemically important (too big to fail, in plain English), there are additional layers of loss absorbing capital, such as a surcharge that varies with size in CET1, a capital conservation buffer, and so on. Now, these are, indeed, too arcane for the public at large to worry about, at least for now.

AT1 bonds carry the risk of abatement, by design, by definition. In order to compensate for this risk that ordinary holders of normal bonds do not have to bear, AT1 bonds offer rates of interest higher than on offer on regular bonds. In this respect, they are similar to catastrophe bonds — CAT bonds in the jargon — that reinsurers issue, to distribute the risk of catastrophes like hurricanes across all those willing to bear it, for a price, of course. CAT bonds typically have short tenor, while AT1 bonds can be perpetual.

There might be a case for claiming that, when AT1 bonds were marketed, it was not made sufficiently clear that these are, in effect, instruments of insurance, which are meant to bear the brunt of mismanagement by those at the bank’s helm. But then, when investors see the higher coupon on AT1 bonds, should they not wonder what the risk is for taking on which they are being offered superior returns?

The decision to write off Yes Bank’s AT1 bonds as part of its salvage operation, in which the RBI persuaded other banks, including SBI, to invest large amounts of fresh equity, after the bank’s losses had virtually wiped out the prior equity, was absolutely justified.

The Swiss Federal Administrative Court felt that the Point of Non-Viability had not been established for Credit Suisse before AT1 bonds were written down. This is a matter of empirical verification. In the case of Yes Bank, there is no question about whether the bank had reached that PoNV.

Let us hope justices of the Supreme Court would fully uphold the public interest in the Yes Bank AT1 bond dispute. If the abatement of AT1 bonds is deemed illegal, then banks put deposits and state funds at risk, by their very existence.

If there were procedural errors in the writing down of Yes Bank AT1 bonds, it makes sense to correct those retrospectively, rather than to hold the entire process invalid. Who is in favour of an operation that was successful but killed the patient, rather than of a bit of seemingly flawed surgery that saved the patient?