.png)

Chandan Jha is an Associate Professor of Finance at Le Moyne College. His work examines the causes and consequences of cultural norms and institutional quality on various socioeconomic outcomes.

Sudipta Sarangi is a Professor and the Department Head of Economics at Virginia Tech. He has been a consultant to the World Bank and FAO, and is the author of Economics of Small Things .

October 27, 2025 at 3:26 PM IST

For much of human history, the idea of sustained economic growth would have been unthinkable. Empires rose and collapsed, but life for ordinary people barely changed. Many inventions changed the way we lived, but not how fast we advanced. The world moved, but slowly. Then, about 250 years ago, everything changed.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics (the Sveriges Riksbank Prize) honors three scholars — Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt — who have helped us understand why. Together, they have shown how the marriage of knowledge and innovations became humanity’s most powerful engine of prosperity, and why that engine keeps running.

Their ideas matter not only to economists but to anyone watching the rise of artificial intelligence with both awe and unease. The questions Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt tackled are: what fuels progress, who benefits, and what gets left behind. These are exactly the ones our generation now faces.

The Shift in Knowing

In the nineteenth century, however, a critical shift occurred when people began asking why things worked. Mokyr calls this “propositional knowledge.” Once people learned why things work, they could apply those principles to create new technologies. For instance, once we understood the principles of thermodynamics, we didn't just improve the steam engine, but created a whole new world of machines.

That curiosity created a feedback loop between science and engineering. Science explained the “why,” engineering applied it to the “how,” and each propelled the other forward. It was this co-evolution — theory feeding practice, practice inspiring theory — that made growth continuous.

Just as important, knowledge itself became public. The Industrial Revolution was followed by an “information revolution”: cheaper printing, mass literacy, and the spread of journals and patents. Ideas escaped their silos. Invention became cumulative. Progress built upon progress.

Mokyr likes to remind readers that Athena’s mythical gift to Athens was an olive tree: a symbol not only of peace but of shared prosperity. That, he suggests, is the true metaphor for modern growth: knowledge planted, tended, and shared.

Creative Destruction

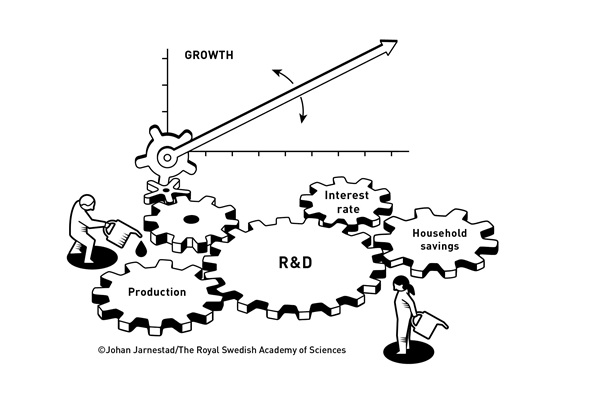

Their model begins with competing firms investing in research and development to innovate. Some succeed, others fail, since innovation is uncertain by nature. But every successful idea replaces an older one, creating a “quality ladder” of ever-better products. In this process, firms literally “stand on the shoulders of giants,” building on what came before, just as Mokyr described.

This continual churn, though often painful, is what keeps economies dynamic. Smartphones replaced cameras and GPS devices; streaming finished off the video rental shop. Every wave of innovation disrupts, yet also pushes the boundaries of what’s possible.

In their model, the solution is a Markov Perfect Equilibrium, a notion used to solve games played over time. Its beauty lies in not requiring the entire history of play; optimal behavior depends only on the current state of the economy.

In this model, innovation drives the growth rate, suggesting the need for policies that sustain this perennial gale of creative destruction. Moreover, as successful firms with better products replace existing firms, there will always be winners and losers. Skills become obsolete, and people with outdated skills are laid off. However, Aghion and Howitt showed that the economy as a whole still grows over time, leading to greater prosperity. Of course, government intervention may be needed to ensure fair distribution.

Their work reminds us that an economy’s strength depends on two things above all: its ability to innovate and its ability to adapt.

Lessons for Today

The story of sustained economic growth is, at heart, a story about human imagination, in our capacity to ask “why,” to learn from one another, and to rebuild the world again and again. That capacity, more than any invention or algorithm, remains our greatest asset.

Finally, the history of economic progress shows that there will always be obsolescence accompanied by winners and losers. It’s something worth keeping in mind as AI reshapes every sphere of our lives.