.png)

Amitabh Tiwari, formerly a corporate and investment banker, now follows his passion for politics and elections, startups and education. He is Founding Partner at VoteVibe.

February 12, 2026 at 11:16 AM IST

Kerala’s 2026 Assembly election should, by all conventional logic, be routine. The state’s voters have spent four decades perfecting the art of alternation. Governments come, governments go. Power shifts hands. Incumbents are rarely indulged. Since 1982, the pendulum has swung with almost mechanical predictability between the Left Democratic Front and the United Democratic Front.

Except once.

In 2021, Pinarayi Vijayan broke the rhythm. Against history, habit and expectation, he secured a second consecutive term for the LDF. It was not merely a victory; it was a disruption of Kerala’s political muscle memory.

Five years later, the question is no longer whether anti-incumbency exists. It plainly does. The question is whether the Congress-led UDF is capable of converting it into power — or whether it will once again find a way to lose an election that appears structurally winnable.

Broken Rhythm

In 2016, the LDF returned to office with 91 seats and 45.4% of the vote, reducing the UDF to 47. That fitted the traditional pattern. In 2021, instead of a reversal, the Left expanded its mandate to 99 seats while the UDF slipped to 41. It was the first back-to-back win for a ruling coalition in forty years.

By 2026, the LDF will have governed for a decade. Fatigue is inevitable. It is also visible.

The December 2025 local body elections gave the UDF its first tangible momentum in years. Polling by VoteVibe suggests that 51.9% of respondents rate the government’s performance as poor or very poor, against 34.5% who see it positively. Price rise, corruption and unemployment dominate voter anxieties. This is classic anti-incumbency territory.

Kerala voters are rarely sentimental about governments that overstay. They are pragmatic, unsparing and politically alert. When they tire of a regime, they usually remove it. But elections are not decided by mood alone. They are decided by organisation, alliances and credibility. On all three counts, Congress remains uncomfortably fragile.

Social Arithmetic

Kerala’s politics has always been anchored in careful social arithmetic. According to the 2011 Census, the state is roughly 55% Hindu, 27% Muslim and 18% Christian. Five districts — Wayanad, Malappuram, Ernakulam, Idukki and Kottayam — together account for 47 Assembly seats where Muslims and Christians form a combined majority.

For decades, this map produced a familiar pattern. The CPI(M)-led LDF drew its core strength from Nairs, Ezhavas and Scheduled Castes. The UDF relied on minority consolidation through allies such as the IUML and Kerala Congress factions. That division is no longer neat.

Performance of Parties in 2021 in Minority Influenced Seats

In 2021, the LDF secured 49% of Ezhava votes, 50% of Scheduled Caste votes and 45%

of Nair votes. More strikingly, it also made inroads into minority constituencies. Surveys indicated that around half of Muslim voters and nearly half of Christian voters backed the Left.

The BJP’s slow but steady expansion in Kerala — modest in seats, meaningful in vote share — has altered political incentives. Most of that growth has come at the UDF’s expense, particularly among Hindu voters who were never deeply rooted in Congress’s ecosystem.

As those voters drift towards the BJP, minority voters have become more transactional, consolidating behind whichever formation appears better placed to block the saffron advance.

In 2021 that formation looked like the LDF.

The result is a tightening vice around Congress: leakage of Hindu votes to the BJP, and wavering minority confidence in the UDF’s ability to hold the line. The LDF’s absorption of the Kerala Congress (M) faction has only sharpened this squeeze.

Leadership Vacuum

The VoteVibe poll reveals something striking about leadership perception: there is no dominant figure towering over the race. VD Satheeshan of the INC leads the preferred Chief Minister ratings at 22.4%, but Pinarayi Vijayan — despite visible incumbency fatigue — remains close behind at 18%. KK Shailaja, widely admired for her handling of the Nipah outbreak and the Covid response, follows at 16.9%. Newly appointed BJP state president Rajeev Chandrasekhar registers 14.7%.

This is an election without a hero. Satheeshan leads a fragmented field more by default than by magnetic pull. Vijayan is a known quantity — respected even by opponents — whose authority within the CPI(M) remains intact, even as succession questions hover and age works against him. The contrast between a steady, experienced incumbent and a fractious, uncertain opposition is one the LDF will seek to exploit relentlessly.

The top three voter concerns — price rise at 22.7%, corruption at 18.4%, and unemployment at 18.2% — all cut against the government. In a neutral contest, such numbers should favour the UDF decisively.

But elections are rarely neutral contests. They are won by parties that can organise, unify, and present a credible alternative. The UDF has the issues on its side, the historical cycle on its side, and the momentum of recent local body elections. What it lacks is internal cohesion and a cadre network that can match the LDF’s discipline. Whether its supporters will actually turn out and act on D-Day remains the central question.

The Congress Conundrum

Haryana in 2024 was meant to be Congress’s comeback moment. The BJP had governed for a decade. Anti-incumbency was evident. Opposition surveys predicted a comfortable win. Congress still lost — not because voters rediscovered affection for the incumbent, but because the party squandered its advantage through infighting, poor candidate selection, and an inability to project itself as a credible government-in-waiting.

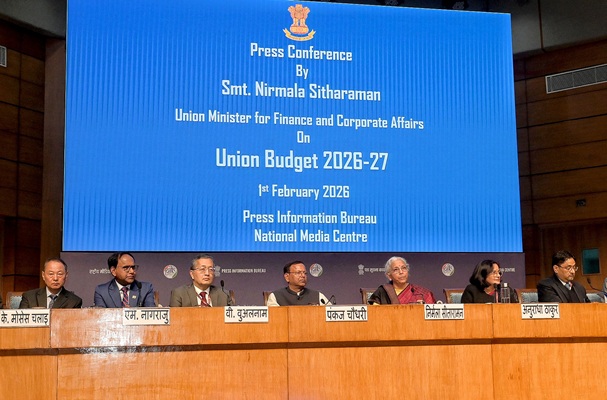

Kerala 2026 carries the same structural anxiety. The January VoteVibe poll places the UDF at 32.7% voting intention against the LDF’s 29.3% — a narrow 3.4% lead — with 15.3% of voters still undecided. That floating vote is large enough to determine the outcome. Crucially, the survey identifies infighting and factionalism as Congress’s single biggest weakness, cited by 42.2% of respondents.

Senior leaders within the UDF are visibly pulling in different directions. The high command has been forced to manage Shashi Tharoor carefully — a nationally visible leader with a strong base in Thiruvananthapuram coming from a Nair family, whose uneasy relationship with the state unit is an open secret. When a party spends more time containing its own leaders than mobilising voters, it is no longer campaigning. It is merely managing risk.

The NDA’s principal challenge, by contrast, is listed as its inability to read Kerala’s political culture — an ideological mismatch rather than organisational decay. That is a different kind of handicap, and arguably a more remediable one over time.

Anti-incumbency is real. History is favourable. The opening exists.

What remains uncertain is whether Congress has the discipline to walk through it. If it does, Kerala returns to its familiar rhythm. If it does not, the pendulum stops — and the Left secures a third term not by persuasion, but by default.