.png)

Karan Mehrishi is an author and economics commentator, specialising in monetary economics. He is also the host of the Talking Central Banks podcast.

December 9, 2025 at 6:10 AM IST

Last month, India’s Ministry of Statistics published GDP data for July-September, surprising analysts and economists alike. The economy expanded by 8.2% in real terms in July-September, the fastest pace in six quarters, on the back of a stronger-than-expected 7.8% in April-June. This strong performance will likely push growth in 2025-26 beyond 7.3%.

Analysts had expected household consumption to falter amid weak private capital expenditure. Typically, such a combination signals slower capacity creation, which can reduce job growth and, in turn, household spending. Given this context, growth was expected to weaken, let alone rise to a multi-quarter high.

A closer look at the GDP components reveals that the supply side, represented by the Gross Value Added at basic prices, grew much faster than the demand side, measured by total expenditure. Notably, ‘discrepancy’ — the difference between GVA-based and expenditure-based estimates — reached its highest level in five quarters. In July-September, the discrepancy stood at over 3.3% of GDP, or ₹1.63 trillion, the highest in seven-and-a-half years in absolute terms.

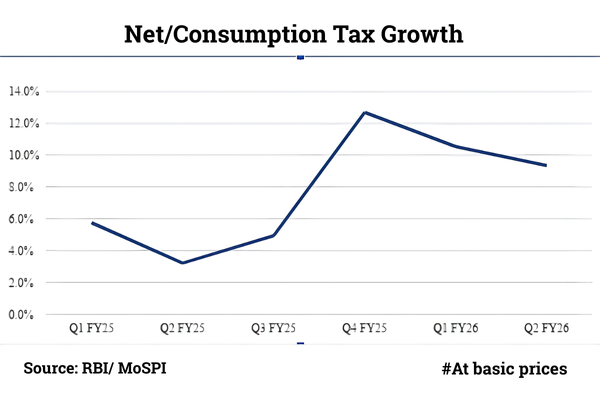

This gap has implications for consumption demand and the expenditure side of the economy, which is concerning for a domestic demand-driven economy like India. Interestingly, this occurred despite healthy growth in consumption taxes in July-September, which rose by 9.3%. Although slower than in the previous two quarters, this growth suggests robust household spending. Yet, it is not fully reflected in the aggregate demand data.

According to the author’s own assessment, while the supply side grew 8.2% in real terms, the demand side grew only 5.1%. This 310-basis-point gap marks the slowest demand-side growth in five quarters, nearly reversing its lead over the supply side from the previous quarter. Domestic inflation, as measured by the implicit GDP deflator, remains at a multi-quarter low, which may partly explain subdued consumption growth.

This conundrum suggests that India is expanding productive capacity — through infrastructure development and efficiency gains — faster than previously estimated, paving the way for future consumption growth and productivity gains. However, this is resulting in a situation where the actual GDP figure might be trailing its potential. A better way to evaluate the Indian economy right now may be to look at it from the supply side rather than the demand side.

However, this supply-side growth is largely supported currently by record government spending, particularly on capital formation, which may not be sustainable if private-sector participation remains weak. The July-September data suggest a weakening appetite for public consumption, but the capital formation figures remain robust and are driven mainly by fiscal muscle.

This possibly cannot continue forever, and policymakers must remain vigilant to ensure that the fiscal deficit limits are respected and the government debt-to-GDP ratio remains sustainable, especially in light of India’s recent sovereign ratings upgrade from BBB- to BBB by S&P.

Looking ahead, October-December may deliver growth of over 7%, driven by the full effects of the GST cut and festive consumption. Historical trends also suggest that the third quarter is often the strongest quarter for GDP growth. Additionally, revisions to the GDP base year may further enhance reported growth as seen in previous exercises.

In conclusion, India’s real GDP growth above 7% is likely to continue, but economic well-being depends on stronger demand-side performance. While supply-side expansion indicates rising capacity and potential, a healthy domestic demand remains critical for a truly balanced and robust economy.