.png)

Calm Hands Steer India Through Policy Storms

Dr. Michael Patra’s new book reveals the inner theatre of India’s central banking—from crisis firefighting to quiet reforms.

Kalyan Ram, a financial journalist, co-founded Cogencis and now leads BasisPoint Insight.

October 27, 2025 at 4:56 AM IST

In four decades at the Reserve Bank of India, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra lived through every convulsion of modern central banking, from the Balance of Payments crisis of the 1990s to the unprecedented lockdown during the COVID pandemic. As Executive Director, MPC member and finally Deputy Governor, he became both practitioner and chronicler of the institution’s transformation from a cloistered craft to a transparent, communicative public body.

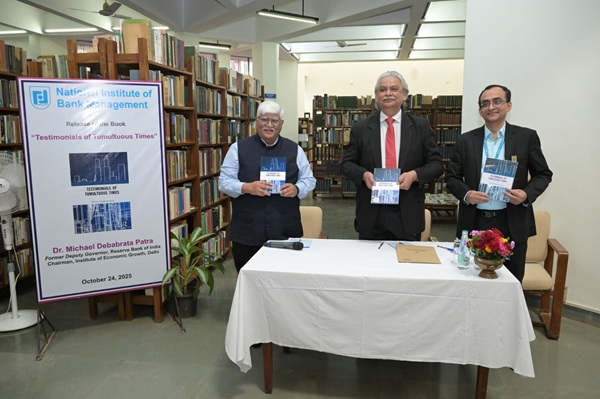

His new book, Testimonials of Tumultuous Times, captures this journey in a series of essays that are at once memoir, policy history, and philosophical reflection.

Patra speaks with the equanimity of someone who has wrestled with chaos and learned to respect uncertainty.

In this emailed interview, he revisits the moments when the RBI operated on the brink, the rescue of the mutual fund industry over a single weekend in April 2020, the fog of decisions taken without precedent, and the moral calculus of saving livelihoods while inflation raged. Policymaking, he says, is a “balance on the razor’s edge between helplessness and efficacy,” a process that extracts its human cost while demanding composure.

Yet his worldview is anchored in optimism.

Conceived in the shadow of the pandemic, the book reaffirms faith in India’s economic resilience and its capacity to finance its own ascent. For Patra, this is “India’s century,” one that must be built on productivity, infrastructure and climate harmony. The same conviction guides his vision of the RBI’s future: adaptive, technology-driven and globally engaged, yet rooted in institutional humility.

In this conversation, Patra reflects on the making of India’s flexible inflation-targeting regime, the evolution of monetary policy communication from secrecy to the “three Es” of explanation, engagement, and education, and the role of humour in easing the weight of impossible choices. The portrait that emerges is not merely of a policymaker but of a writer who believes that well-chosen words, like sound policy, can calm markets and lift spirits alike.

Read on:

Q: Your book Testimonials of Tumultuous Times seeks to capture the dilemmas and trepidations of central banking over a wide range of themes that are critical not just to central bankers but also to the wider conduct of public policy. What was the main motivation for writing this book?

The scales are always heavily tilted towards ineffectiveness; hence, narrow windows that open up for rebalancing towards capability become harshly goal-driven to secure the welfare of society. That is why policymakers may appear hard-hearted. A favourite joke of Mario Draghi, former President of the ECB, who went on to become the Prime Minister of Italy, comes to mind. A man needs a heart transplant. The doctor offers the heart of a five-year-old boy. “Too young,” says the man. “How about the heart of a 75-year-old central banker?” “I’ll take it.” “But why?” “It’s never been used.”

This continual balancing of conflicting pulls takes its toll. Hence, the life of a central banker is one of continual self-sacrifice. With every policy action or inaction, a bit of the soul is extinguished forever. My book is an attempt to describe this adrenaline-pumping octane-sniffing life.

Q: On reading the book, one prominent aspect that runs like a common thread through it is a sense of hope, of optimism. Why is this so, especially in the face of the extreme events that have characterised the period covered by the book?

The RBI’s response was somewhat unique among central banks. In order to ensure essential functions like supply of currency, banking, functional markets, etc., a bio-bubble was created in which 200 officers, staff and technicians were kept in complete isolation to keep these basic functions going just in case the Governor, Deputy Governors and other senior management succumbed to COVID. Every day, the management team would don masks, sanitise themselves, maintain social distancing, say a prayer and launch a counter-attack against the pandemic. It was a step in the dark. We had no standard operating procedure or template. The last pandemic of this scale and severity was 100 years ago — the Spanish flu. Although India was one of the worst-affected countries at that time, as in this pandemic, we had erased its memory from our collective psyche. So, we went about literally inventing policy measures, throwing out lifelines to the rest of the economy. I still remember: India’s mutual fund industry was saved over a weekend — on a Saturday, a big mutual fund went bust and contagion spread across the industry, threatening to take it down in entirety due to the panic redemptions. On Sunday, we plotted our response. On Monday, we put the entire industry back on its feet.

Many of those moments were very lonely ones, as they were for the entire nation. So, in those times of extreme isolation, I thought: what can I do to give the nation some hope, some relief, that this too shall pass? To my astonishment, I found that there are many things to live for, to look towards for a better, brighter future.

India is the youngest nation in the world and the largest at a time when the rest of the world is ageing. It is self-financing its economic progress. It is an oasis of macroeconomic and financial stability amidst tsunamis of high turbulence. India has much to aspire for, and we should pack our dreams with ambition. What do we need: a highly productive and skilled workforce; the world’s best infrastructure, a global manufacturing and export hub, an internationalised rupee like the Indian people; living in harmony with the climate; harnessing new technologies to give our people the best living standards as we strive to achieve our developmental aspirations as a nation.

This became the first part of the book, the story of India rising. It provides the backdrop for the rest of the book. I argue that India’s time has come. This is going to be India’s century. The history of the world, according to the late British economic historian Angus Maddison, tells us that right up to 1700 AD, India was the world’s economic powerhouse, running a trade surplus with the rest of the world, until the advent of the British East India Company. There is no reason why that lost glory cannot be recaptured. I will not live to see it, but succeeding generations will if they want to.

Q: A substantial part of the book is devoted to the design and implementation of monetary policy. What are the salient features of that experience?

You are right. This is an area in which, in a sense, I grew my wisdom teeth and lost them, too. In any central bank, monetary policy is regarded as the most difficult function where angels fear to tread. The former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, the renowned Ben Bernanke, once described an economy as an automobile, the monetary policy committee as the driver, and monetary policy actions as taps on the accelerator or brake. I quote him in the book. When the economy is running too slowly, the committee increases pressure on the accelerator by lowering the policy rate, thereby stimulating economic activity. When the economy is running too quickly, the committee presses down on the brake by raising the policy rate. In real life, the driver cannot determine the speed of the automobile. The road ahead is also not visible. ‘The car has an unreliable speedometer and a foggy windshield, and it responds to the accelerator or the brake with some delay. In sum, not a vehicle for inexperienced and faint-hearted drivers.’

Within the area of monetary policy, the most difficult part that monetary policy makers resist most strongly is changing the regime. By regime, I mean a framework consisting of some first principles, some processes, and an operating procedure that facilitates the transmission of policy actions to the rest of the economy. The framework allows policymakers to map instruments like the policy interest rate to the goal, such as employment or inflation. In my book, I describe how in 2016 (actually in 2015 because we signed an agreement with the government to activate it even before it was legislated into law), we changed India’s monetary policy regime and adopted flexible inflation targeting.

Why is it significant? First, the international context. It is a framework which has become operational without a formal theory. It has survived the test of time; all other regimes have either fallen by the wayside or hung on as endangered species. Countries practising inflation targeting number more than 45 and counting. Although it began in New Zealand and was first adopted in the Anglo-Saxon world, it is increasingly finding favour among developing countries, which outnumber developed ones as adopters. And to date, there has been no country that has dropped out.

Why is it significant for India? First, it was criticised and rejected by former Governors, Deputy Governors, and some in the government of that time. It was called a fad, a passing fancy, a blinkered approach, a single-minded obsession. Second, it was conceived, drawn up and operationalised by a dedicated group of RBI officers, whom I hand-picked. Third, it has been described by the Prime Minister as one of the most significant policy reforms in India. Fourth, for the first time, the Governor relinquished his power to decide the policy action and ceded it to a committee in which decision-making became collegial and by majority vote – unheard of in India. Fifth, the RBI and the committee began to communicate to the public why they did what they did, whether they failed or passed, and why, and how they intend to address such deviations in the future. In doing so, they became accountable to the nation. Today, everyone knows what the inflation target is and who is responsible for it.

In the first five years of its operation, it was a tremendous success. During this period inflation averaged 3.9%, a shade lower than the target. India’s growth averaged 6.5% while world growth was below 3%.

Critics began to grudgingly acknowledge that it was a good policy, but some ascribed its success to good luck because international commodity prices declined. The Governor, under whose watch it was instituted, commented in public that the framework has not been tested. And then came trials by virus, by fire, by panic and by markets — the once-in-a-century pandemic, followed by wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, aggressive monetary policy tightening worldwide, bouts of high turbulence in financial markets, leading to failures of banks in some jurisdictions and now the Trump tariffs.

Inflation did exceed the target substantially during the pandemic when the RBI prioritised lives and livelihoods over price stability. Again with the wars, inflation surged all over the world, provoking one of the most aggressive and synchronised tightening of monetary policy in human history. Eventually, it was the flexibility embedded in the framework design, the dedication and perseverance of those who operated it, and the reforms they pushed in financial markets and in the financial inclusion of people that led to the taming of inflation. All these trials and the indomitable spirit of the tough getting going are described in separate chapters of the book.

Q: You describe dealing with the challenges and trade-offs involved in conducting monetary policy with a certain light-heartedness that seems to underplay this adrenaline-driven experience, as you put it. What is the secret of this pleasant side?

In my book, I tell the story of a Chairman of the US Fed who just assumed office and made a courtesy call on his predecessor to seek guidance on how he should perform his duties. The predecessor handed the new Chairman three envelopes with the advice that whenever he found himself in trouble at work, he should open the envelopes, one at a time. Each would have advice on what to do. In a year’s time, when the new Chairman found himself under attack, he opened the first envelope. It said: “Blame me.” So, the new Chairman blamed his predecessor. After some time, the new Chairman came under attack again. He opened the second envelope. It said: “Blame the government.” So, he did that. After some more time had passed, he came under attack again. So, he opened the third envelope. It said: “Prepare three envelopes.”

Another anecdote I have recounted in the book is that a person visiting a country finds himself stuck in a traffic jam because of a large crowd gathered on the street. He asks a police man what is going on. He is told that the central bank governor is so depressed about the state of the economy that he has decided to douse himself with petrol and set himself on fire. So, in sympathy, the crowd has gathered to take out a collection for him. “How much has been collected?” asked the man. The answer: “40 litres.”

Monetary policy, at its core, is all about informed human judgment constrained by high uncertainty, which cannot be replaced by mechanistic models or rules. All its processes inherently imbue the lighter side of life.

Q: As the conduct of monetary policy undergoes a silent transformation worldwide, there is also a sea change in the attitude of central bankers towards the communication of monetary policy to the wider public. You have also addressed this issue in your book. What are your views on the subject?

A: Today, monetary policy announcements, all over the world, are perhaps among the most avidly watched, heard and debated events in the public domain. Monetary policy makers are mobbed like film stars and their every word and action is scrutinised closely in the media. In my time in the RBI, even the colour of our ties was taken as hinting at the underlying policy strategy and stance. Even ahead of the actual announcement, newspaper columns and television shows are sizzling with second-guesses of what the central bank will or will not do. Projections are revised, and the balance of risks is re-titled. Shadow monetary policy committees take positions. Curve fitting the central bank commences — is it behind the curve? Bird-like postures are assigned to monetary policy makers — Hawk? Dove? After the announcement, financial markets immediately start repricing financial assets. Financial institutions reassess interest margins. Depositors and businesses exert conflicting pulls on public opinion. Questions fill the air on rate movements, how much, and on shifts in stance.

Yet, it was not always so. Until the early 1990s, secrecy was the byword of monetary policy. Central banks used to be shrouded in mystery, and they also believed that they should be so. The conventional wisdom was that monetary policy makers should say as little as possible and if they had to speak, they should say it cryptically. Monetary policy was regarded as a complex craft, with access to it and its execution confined to the initiated elite. It was widely accepted that it is impossible to describe or explain monetary policy in explicit and intelligible words and sentences, and hence, the less explained, the better.

From the 1990s, this monetary mystique was gradually dispelled, but it was replaced by what is called ‘constructive ambiguity.’ A less flattering description of this is ‘mumbling with great incoherence.’ Alan Greenspan, then Chairman of the US Fed, perfected it into an art form. Everyone has a favourite quote from Greenspan; mine is: "I know you think you understand what you thought I said, but I am not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant." He achieved a style of speaking regularly while communicating little. There was an underlying rationale to this opaqueness. Greenspan believed that a language of purposeful obfuscation is much better than not responding; or saying, “no comments”; or “I won’t answer”.

By the 2000s, central banks gave up mumbling and started to become more explicit. This also reflected broader societal changes. Considerations relating to democratic accountability took precedence over constructive ambiguity. The great transformation came after the global financial crisis. With interest rates at the so-called zero lower bound, central banks lost their instrument. With balance sheets bloated by unconventional ultra-accommodation, they lost their independence. Communication got elevated to the status of a monetary policy instrument. Forward guidance was actively used by central banks. Explanation, Engagement, and Education became the three Es of central banks. This shift came in handy during the pandemic when people looked to central banks for support as well as the reassurance that they would do all they could to prevent loss of livelihood and restore stability in financial markets and institutions.

When inflation checked in from the second half of 2021 and rose to levels not seen since the 1970s and early 1980s, the most aggressive and synchronised tightening of monetary policy was undertaken. Suddenly, the lessons of the GFC and the pandemic were no longer relevant. Forward guidance stirred up bouts of turmoil in financial markets and spillovers to emerging markets. Monetary policy encountered the ‘cacophony problem’ — too many disparate voices that confuse rather than enlighten the public. While the utility of forward guidance at very low policy rates is unambiguously proven, its efficacy at higher rates is questionable.

In essence, therefore, the story of monetary policy communication is the story of the evolution of the conduct of monetary policy itself.

Q: A part of the book chronicles the journey of the Indian financial system from fragility to resilience. What were the major milestones of this journey?

India was among the first countries to rebound from the crisis and regain normalcy. A V-shaped recovery fuelled robust optimism about double-digit growth. Banks, the principal financial intermediaries in India, launched into financing infrastructure development while lowering appraisal and lending standards. Soon, impaired loans started piling up on banks’ balance sheets, eventually constraining their ability to lend. Deep surgery became urgent: recognition of the magnitude of impairment; recapitalisation; resolution through a new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, among other instruments; intrusive regulation and supervision; and the ascent of financial stability in the hierarchy of national policy objectives. The results of this ‘cold turkey’ approach are now becoming visible among banks and other financial institutions, in the form of a steady decline in non-performing loans, increasing provisions against losses, strengthened capital and liquidity buffers, and a return to profitability. India’s financial sector is now sound, vibrant and well primed to take on the financing requirements of India’s century.

A key but silent role in this turnaround has been played by deposit insurance in boosting the confidence of depositors in India and preserving financial stability. A landmark legislative amendment has made India unique in the world by mandating that interim deposit insurance payments be made within 90 days of an insured bank going into regulatory review, even prior to liquidation and/or amalgamation.

Q: The period of your office as Deputy Governor also coincided with some important international developments in which India assumed an important role. Could you describe those times and how they shaped India’s interface with the rest of the world?

Q: Looking ahead, how do you see the future of central banking in India?

Modern technologies such as application programming interfaces, artificial intelligence and machine learning, biometric-based identification and authentication, cloud computing, and distributed ledger technology are currently powering innovations in the financial sector worldwide. Technological advances are redefining policy-making, re-engineering work processes and procedures, building new capacities and, more generally, rethinking approaches to various policy functions. We must adapt to Industrial Revolution 4.0 as we face new demands of citizens for greater speed, convenience, and affordability. New products and new providers, including those such as fintech and bigtech are making life smarter, but they also confront us with the associated risks. While managing the risks, policy makers must pay heed to the fact that regulations can stifle or foster innovation. We must open our minds to the power of innovation and the cross-fertilisation of ideas and experiences while being mindful of the inherent challenges. Cooperation and dialogue with other central banks and regulators, as also with other stakeholders, both domestic and international, are imperative if we are to navigate the ceaseless tides of innovation.

Q: Your Deputy Governorship overlapped with Shaktikanta Das holding office as Governor of the RBI. How do you evaluate that experience? What kind of impact did he have on your views and work?

As I have stated in the book, he is perhaps the only one other than I who has read every word of the book. As is well known, he is extremely savvy with the press and media. So, I think because of that, he was very protective of me. He would sift through my writings with a critical eye and pens of many colours of ink, ensuring that I remained politically correct. He would encourage me to go on working when my spirit flagged. I think somehow, he believed that I had it in me. I hope my book has done some justice to that confidence he reposed in me. In the book, I have expressed my fond dream to be a small part of his book when it is written.

Q: Any final thoughts?