.png)

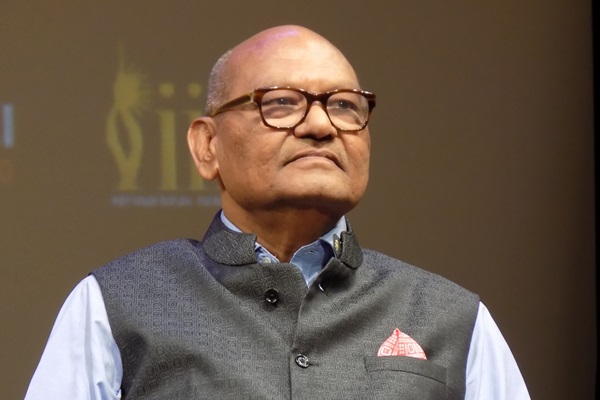

Dev Chandrasekhar advises corporates on big picture narratives relating to strategy, markets, and policy.

May 2, 2025 at 7:25 AM IST

In 2024–25, Vedanta Ltd reported one of its best years in recent memory, with consolidated net profit jumping 172% to ₹205.4 billion and revenue hitting a record ₹1.5 trillion. The surge was driven almost entirely by its aluminium and zinc businesses, where both volumes and cost performance showed marked improvement.

Aluminium output rose to an all-time high of 2,422 kilotonnes, supported by a 9% increase in alumina production from a new processing train. Unit costs, excluding alumina, fell to a four-year low of $920 per tonne. At Hindustan Zinc, mined and refined metal production reached historic highs of 1,095 kilotonnes and 1,052 kilotonnes, respectively, with January–March quarter costs falling to a 16-quarter low of $994.

The traction extended to other metals: iron ore production rose 12%, and copper cathode volumes edged up. The result was a 37% year-on-year increase in consolidated EBITDA to ₹435.41 billion, and free cash flows helped push cash and equivalents to ₹206.02 billion. Even though net debt as of March 31 was a high ₹532.5 billion, a worryingly third of annual revenue, net debt-to-EBITDA improved to 1.2x, the best level in nine quarters.

Yet while metals did the heavy lifting, oil and gas weighed heavily on the portfolio.

Production fell 19% year-on-year to 103.2 thousand barrels of oil equivalent per day. Realisations softened to $74.2 per barrel, and energy EBITDA halved to ₹4.66 billion. That segment now contributes just 10% of group profits, down from 25% three years ago.

Vedanta blamed natural field decline and delays in well development—standard issues, but harder to overlook as the gap between businesses widens.

The divergence is driving strategy. Vedanta plans to split into six listed entities by September 2025, a move aimed at isolating its stronger businesses from the weaker ones. If successful, the metals business could attract a sharper valuation. But the standalone oil and gas company will likely face closer scrutiny, particularly with a reserves replacement ratio below 50%, and more than 85% of production coming from ageing onshore fields.

Three markers will determine how the story unfolds. One is whether Vedanta sticks to its September 2025 demerger timeline. The second is whether the long-delayed Alkaline Surfactant Polymer programme lifts oil and gas production in the first half of 2025–26.

The third is bauxite: delays at the Sijimali mine could narrow aluminium margins just as metals are carrying the group.

Metals saved the story in 2024–25. But unless energy shows signs of revival soon, the demerger might do little more than confirm that Vedanta’s future lies firmly in its smelters—and not its wells.