.png)

Gurumurthy, ex-central banker and a Wharton alum, managed the rupee and forex reserves, government debt and played a key role in drafting India's Financial Stability Reports.

April 9, 2025 at 4:17 AM IST

Amidst the US tariff tantrums, another avowed objective of the current US administration is deregulation, and softer bank regulation is a subset of that agenda.

The US big banks especially, had been at unease at the ever-evolving and stringent Basel framework, notably the so-called Basel Endgame Proposals.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, while speaking at the Economic Club of New York recently, declared that the financial regulatory agenda needed "a fundamental refocusing of supervisors' priorities". In the same vein, Travis Hill, acting FDIC head, speaking elsewhere, felt that the regulators need to be more focused on the real fundamental financial risks and less on the administration around that. That sounds reasonable —at least when judged by the words alone.

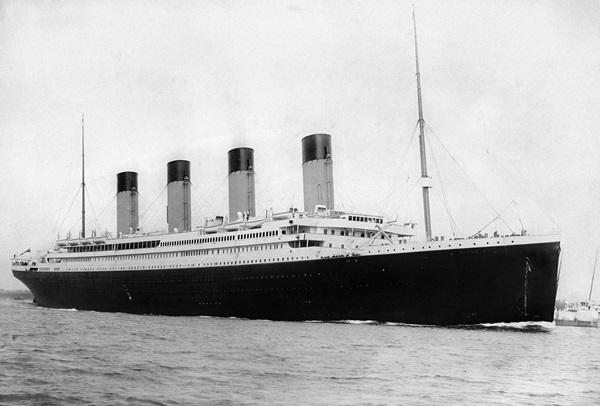

After the Titanic incident, it was decided as part of the International Convention for the Safety of Life At Sea that passenger ships would need to carry sufficient lifeboats to accommodate every passenger on board. The very next year, passenger ship SS Eastland rolled over onto its side even as it was docked in the Chicago River, killing 844 people. One reason for the disaster was the weight of the lifeboats themselves.

There is a feeling, specifically in the US, that financial sector regulations have reached such a level as to invoke the Eastland syndrome to make a point. With the new administration in place, there seems to be a backlash against bank regulations which, since the global financial crisis, through several iterations, have been viewed as the bulwark against bank failures and systemic risk.

While the proponents of a perennial tweaking and finetuning of Basel bank regulations feel banks have become stronger and less vulnerable as a result of such tweaks, sceptics would argue that they have become so stringent as to make banking an unviable business, and that the increasing capital requirements impinge upon credit delivery and economic growth.

Critics also feel that the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the ‘rule-setting body’ has grown into a bureaucracy and the resulting compliance costs imposed by never ending iterations of such rules have a strong bearing on banks’ performance, operational efficiency, and innovation. The key is to strike a balance between regulation and innovation.

The evolution of bank regulation is tied to the evolution of the oxymoronic ‘limited liability banking company’—a peculiar form of corporation in which liabilities are limited to shareholder equity despite the fact that most of bank liabilities are held in the form of public deposits, which are committed to be payable on demand. The business of banks, however, tends to be highly leveraged, with a high proportion of outside liabilities to owners’ capital, in which the accumulation of loans, unmindful of associated risks, raises bankruptcy costs.

According to John Kay, “the changed structure of the finance industry from partnerships to limited liability corporations effectively transferred a degree of responsibility for risk management from firms to regulators”.

The resultant dilemmas and evolving tensions could be best explained by Edward Kane: “Bankers understand the financial safety net as a politically enforceable implicit contract that they have negotiated with their national governments” and “not as something external to their balance sheets”... “lobbyists create a taxpayer put by creating an excessive fear in the minds of regulators of letting banks’ accounting decisions or health be called into question”—hence the call for stringent regulations by regulators!

Basel accords are legally nonbinding but mutually agreed upon and enforced—with some discretion exercised in favour of national interest that could be termed as “glocal”—by bank regulators.

The Basel accords, first proposed in 1974, shifted the focus from the liability side of the bank balance sheet (leverage ratio) to the asset side, estimating the impact of potential credit, market and operational risks that could result from their asset holdings (mainly loans and investments). Consequently, banks were expected to retain a certain proportion of their risk weighted assets as capital—an approach different from the liability side focus, in as much as it is not the size of the assets but the size of the risky assets. While this appears esoteric—and everything that is esoteric must be wiser—it brought in much subjectivity in assessing what and how much risk is embedded in an asset portfolio.

But the Global Financial Crisis proved that the second version of the accords (Basel II) had been ineffective in countering a situation in which banks were overleveraged and undercapitalised—not solely because of insufficient capital, but because of a bloated asset portfolio with underestimated risks. This led to the development of Basel III, with stricter capital requirements. While the EU and the UK broadly welcomed the changes, many in America felt that capital requirements would be disproportionately increased.

US banks feel that stress tests are good enough to gauge their inherent strength and the fact that they steered through the pandemic is a robust sign of their health. There was a concern even in India that the higher capital requirements will constrain a bank’s credit dispensation abilities and push banking activity towards less-regulated and unregulated players, thus increasing systemic risk.

Whatever happened leading to the GFC was the result of regulatory dialectics—a perennial tension between regulation and innovation. According to Edward Kane, regulatory dialectics operate through a set of intuitive rules, as the financial market regulation is an endless process with both the regulator and the regulated making alternative moves; and that the lag between regulation and avoidance is shorter than the lag between avoidance and regulation!

According to the “regulatory dialectics” framework, financial market players in the dialectics model exhibit their average adaptive efficiencies in the following order:

• Less regulated players move faster and more freely

• Private players move faster and more freely than governmental ones

• Regulated players move faster than the regulators

• International regulatory bodies move more slowly and less freely than all other players

While regulators have a duty to protect consumers, because of the nature of adaptive efficiencies discussed above, there often arises a situation, as articulated by Kane, whereby…“(In the US), strategies for dealing with regulation-induced innovation and for disciplining the institutions that recklessly spawned these plagues have been assigned to teams of incentive conflicted and understaffed regulators to work out”. The reaction from the regulators could be an overkill given the constraints they face, notably limited skill sets and a lack of nimbleness.

While it is easy to navigate through a rule based global order, one problem is: what if the rules are set by those who are ahead in the race? To be fair, Basel rules give enough scope for local adaptations, though the compulsions to be in that elite club often overlooks local constraints. There was a time India used to boast that the local banks were to hold higher capital ratios than what was set by the Basel Committee. Of course, capital comes at a cost—particularly along the “efficiency-redundancy” paradigm.

Sceptics believe that standardised rules and market-sensitive risk management practices have created a landscape in which risks increase rather than diminish during stressed times. Rules that govern liquidity risks, for instance, may have upended the basic objective of banking, namely maturity transformation, where banks take liabilities (most of which are payable on demand) for shorter durations than that for which they lend. Strictly rules-based systems often overshoot, given everyone’s urge to book losses during distress—leading to what Avinash Persaud calls “Liquidity Blackholes”.

But even as regulators move from a rule-based to a principle-based framework, certain regulatory challenges remain. This is true when trying to extend bank-like regulations to non-banks and smaller banks, since the structures of these firms—especially fintechs—are not comparable with those of larger regulated entities. For all that, supervisory benchmarking will still be required so that principles—through targeted and transparent supervisory interventions rather than opaque regulatory pronouncements—are applied consistently across entities.

There is also this prevailing view that the increased focus on quantifiable risks has diminished the supervisory skills at regulatory agencies, especially in a regime where the regulatory and supervisory functions are separated by more than a division of labour. Some even believe that supervision has become a process of checking the box without proper validation. This may help explain why so many audits are initiated for the same purpose—at comparable institutions and sometimes even at the same entity—over and over again. Eventually, as with a major Indian fintech not very long ago, only the revocation of a licence puts such a matter to rest.

With regard to non-quantifiable risks, no one knows how to tackle operational risks as no amount of capital can really address misgovernance or malfeasance. As a result, supervision is restricted to post-facto investigation. Oftentimes, the lines that separate credit and market risks from operational risks are blurry.

Ultimately, there’s no doubt that better supervision, stricter compliance, and more robust capital adequacy rules are well-intentioned. The trick lies in ensuring that good intentions do not override other considerations—potentially leading to an irremediable Eastland syndrome.