.png)

Banker Emeritus writes on monetary affairs with the calm of experience, a sceptic’s eye, and just enough distance to say what others won’t.

April 11, 2025 at 9:21 AM IST

At the April 2025 monetary policy press conference, when asked about action against auditors over IndusInd Bank's accounting irregularities, RBI Governor Sanjay Malhotra retreated behind a familiar shield, saying the central bank does not comment on individual institutions.

A more pressing question that remains unasked is what accountability exists for the central bank’s own inspectors who fail to spot the glaring red flags?

At the same conference, Deputy Governor J. Swaminathan said the central bank wouldn't miss a good crisis to push for change.

That change may need to start from within—specifically, with the RBI's supervisory function.

The cost of waiting for crises to trigger reform is rising. With India’s banking system increasingly complex and digital-first, supervisory lapses are no longer merely reputational—they can quickly snowball into a systemic stress.

Recent disclosures at IndusInd Bank and fraud at New India Co-operative Bank underscore a familiar problem. RBI inspectors failed to flag critical issues, which came to light only through whistleblowers or belated voluntary disclosures. Far from isolated incidents, they expose a deeper malaise plaguing the RBI's supervisory architecture—one that can't be resolved by tweaks and tokenism

Tick-Box Trauma

Importantly, there has been disquiet about how RBI supervision operates. Inspectors often focus on trivial lapses while missing not only systemic weaknesses but also significant idiosyncratic risks that have the potential to become systemic, through sentiment contagion, network effects and moral hazard.

Privately, most senior bankers complain about the conduct of RBI inspection teams. They say inspections often devolve into procedural wild-goose chases, driven by cherry-picked data and box-ticking obsessions. Teams are said to arrive or call at odd hours, demand excessive documentation, and sweat the small stuff while overlooking bigger risks.

Worse, this box-ticking culture erodes mutual respect between supervisor and supervised. Risk flags are often drowned in procedural minutiae, discouraging candour and creating a perverse incentive for banks to manage the inspection rather than the risk.

It is gathered that many supervisory teams demonstrate only a templatised understanding of risk frameworks, typically shaped by their most recent experiences rather than by enduring principles or global best practices. In the IndusInd case, inspectors failed to distinguish between acceptable hedge accounting practices and material deviations from global standards. Other banks had implemented similar structures but within globally-accepted frameworks.

No such contextual learning or benchmarking was evident from the supervisory side. Poor product-level understanding is alleged to be an endemic weakness in RBI’s oversight process.

Worse still, it appears there is often no meaningful review mechanism within supervisory teams themselves. Senior officers, bankers say, routinely act as mere conduits—postmen, not reviewers—passing along juniors’ findings without applying any independent judgment.

Every banking mishap in India seems to follow a tired script: crisis, committee, amnesia. Following the Punjab National Bank debacle, there was talk that the RBI appointed the Malegam Committee to investigate and recommend safeguards. The report has not seen the light of day. Similarly, there were rumours of another high-level internal review committee—possibly including RBI board members—examining the supervisory framework. But if this was true, it yielded no public outcomes.

Regulation Vs Supervision

The RBI’s separation of regulation from supervision, typically assigning supervision to an industry veteran, while regulatory functions remain with a homegrown insider has created regulatory silos between deputy governors. Rather than complementary functions, these departments operate in isolation, with insiders alleging turf wars and blurring accountability. Insiders also speak of internal conflicts between the two departments, which work in silos rather than as collaborative units.

The RBI has invested heavily in modernising its supervisory tools. It moved from traditional compliance-based oversight to risk-based supervision (RBS). Systems like OSMOS (Off-site Monitoring and Surveillance System) and COSMOS (Centralised Online Surveillance Monitoring System) were introduced to enable the early detection of vulnerabilities. A Board for Financial Supervision was also created.

Yet, evidence of their efficacy is scant.

Collecting voluminous data and then relying on the supervisors' individual interpretations of it—often half-baked or flawed—is headache-inducing for banks. It creates more confusion than clarity.

Critical questions remain: Is the voluminous data collected through these systems being put to timely and effective use? Are RBI's training institutes delivering meaningful capacity-building, or are they glorified sinecures?

It may be worth noting that CAFRAL was supposed to evolve into a world-class advanced financial learning and research institute. It is understood that it, in turn, appears to be competing with other training institutes with a captive audience.

Has RBS become just another buzzword, more about form than foresight?

The RBI also talks a good game on modernising supervision with fashionable concepts like REGTECH, SUPTECH, artificial intelligence and machine learning; Yet it remains unclear how deeply these technologies have been integrated into actual supervisory practice with some observers noting that one hardly gets to see much visible outcomes, other than offering a few contracts to global consultancy firms.

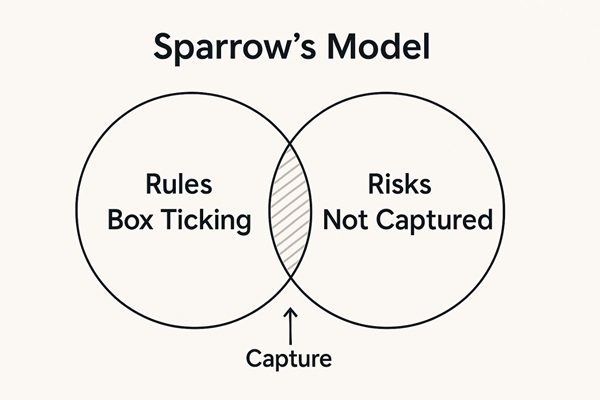

A useful way to visualise the gap is through the ‘Sparrow Model’—two intersecting circles, one representing rules and the other, risks. The overlap is effective supervision. The non-overlapping left side is mere box-ticking; the right, known but unaddressed risks. Much of RBI's effort appears stuck on the left—procedural nuisance without real insight, echoing the old audit maxim: a watchdog, not a bloodhound. What we now have is the worst of both.

Accountability Vacuum

While regulation tweaks continue, sometimes excessively, supervision lags.

Ironically, the global standards-setting body calls itself the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision—a reminder that supervision should be prioritised even as most of the regulations are coming from Basel and that regulation and supervision should ideally move in tandem.

In India, even public consultations on regulatory changes have become performative. According to industry voices, even constructive feedback is sometimes met with institutional hostility.

The feedback mechanism is itself deeply flawed. Feedback often flows through personal equations and informal channels. There is no structured and comprehensive approach for institutions to raise concerns without fear of being marked difficult.

Most prefer selective appeasement over frank engagement.

Concerns about the conduct of supervisory teams are also growing. Bankers speak in hushed tones about heavy-handed or inconsistent inspection practices.

There also seems to be no formal feedback or grievance redressal system to hold supervisory staff accountable. While the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission proposed a common appellate tribunal for financial regulators, RBI has so far remained outside its purview.

This exclusion has created a curious asymmetry: other financial regulators face appeal mechanisms, but the RBI’s supervisory wing remains largely unreviewable, answerable only to itself. In a modern regulatory state, this is increasingly untenable.

There is a strong case for a transparent feedback mechanism—and more crucially, an independent appellate structure—to review both supervisory and regulatory decisions. There are also cases where the RBI may have a conceptual disagreement with a bank on accounting or governance matters—and that is legitimate. But such disagreement should not automatically imply fraud or misconduct. Nuance is vital.

Just as banks are held accountable for their actions, so too must the supervisors and regulators whose decisions and oversight—or lack thereof—shape systemic outcomes. An appellate body that allows structured review of both inspection outcomes and regulatory frameworks would enhance trust and introduce much-needed checks and balances into the system. After all, if banks must answer for their lapses, why not the watchdogs as well?

If Caesar's wife must be above suspicion, India’s financial regulators should be held to the same standard.

Judgment Calls

The RBI occasionally overreaches into boardroom decisions clearly within a bank's operational autonomy – not to say that governance at all boards is of impeccable quality. If the regulator second-guesses such decisions, should it then also be held responsible for the consequences? Supervision must distinguish between poor governance and honest business errors. This creates a troubling liability paradox. The RBI can influence management decisions without bearing the consequences of those decisions—a privilege few others in finance enjoy.

At the heart of it all is a lingering question: Is the Indian banking system stable because of RBI supervision or despite it? The central bank's Financial Stability Reports often give the impression of calm and control. But they are systemic assessments, not audit summaries.

India aspires to be a global financial centre, yet such ambitions demand regulatory maturity as also a matured growth of its financial institutions. Supervisory opacity, procedural rigidity, and lack of internal accountability risk eroding global investor confidence in the very plumbing of the financial system.

The next evolution of RBI's supervision must address fundamental issues: effective utilisation of collected data, accountability for inspectors, a culture of dialogue over diktat, and a genuine shift towards forward-looking risk detection.

Without such reforms, every banking crisis will represent another missed opportunity—the regulator perpetually missing the woods for the trees, wasting yet another “good crisis”.