.png)

Mahendra Ved is a senior journalist. He worked at Times of India, Hindustan Times, and United News of India.

May 8, 2025 at 9:02 AM IST

The India–Pakistan military stand-off on May 7, 2025, is unprecedented in that both sides have claimed to have inflicted damages without breaching the land border. It gives the impression of a strategic stalemate marked by mutual signalling and calibrated damage, with open prospects of further fighting.

Both governments have publicly proclaimed their readiness to fight but appear conscious of the risks and limitations of escalation. Despite their history of prolonged conflicts, the compulsion to remain below the “nuclear threshold” and intense international pressure act as structural constraints on military adventurism.

This may remain a drawn match. Major powers and regional actors invested in regional stability are unlikely to allow either side to decisively tip the balance.

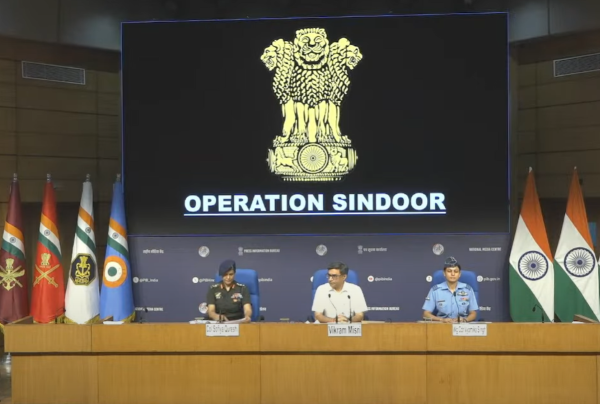

In any case, with Operation Sindoor, India maintained that its response was calibrated and non-escalatory, aimed solely at dismantling terrorist infrastructure. Officials emphasised that the strikes were confined to training camps and launch pads used by terror groups, and that no Pakistani military installations were targeted. The objective, according to India, was to deliver a firm message without provoking a wider military confrontation.

What Next?

On the surface, Pakistan may attempt to absorb the strikes without immediate escalation, relying on diplomatic avenues and media narratives to manage fallout. Although India has struck terror infrastructure and targeted Masood Azhar, these launch pads can be rebuilt once the temperatures cool down.

If cross-border hostilities taper off and missile exchanges remain limited or symbolic, India may pursue pressure through non-kinetic levers—such as revisiting Indus water arrangements or intensifying its diplomatic offensive.

But Pakistan, where 22% of GDP is derived from agriculture, has long proven adept at internationalising such issues to generate sympathy. It did so effectively in 1972 when dealing with the issue of prisoners of war, and again while attempting to cast India in a negative light.

The prospects for bilateral dialogue remain slim. Politically, the Modi government is unlikely to suffer. It may even benefit from a nationalist wave of support. Pakistan, by contrast, tends to unify against perceived threats from India, and the military could further consolidate its hold over civilian institutions.

Economically, both countries face costs. Pakistan, already in distress, may slide further—but is likely to receive backstop support from geopolitical allies. India, despite having an economy nine times larger, would still need to divert capital from infrastructure and productivity-enhancing investments toward defence.

Indian stock markets did not react sharply on May 7, but an undercurrent of concern was evident. On the first day of heavy shelling in Kashmir, the Sensex and Nifty briefly dipped before recovering. The rupee slipped around 0.2%. In contrast, Pakistan’s KSE-100 index plunged 5.8%.

Market volatility may persist, shaped more by perceived intent and signalling than by battlefield outcomes. Investor risk appetite could wane, particularly among foreign portfolio investors. Pakistan may absorb deeper financial shocks, though it has historically managed external support through deferment or debt relief.

The aviation sectors in both countries could experience lingering disruptions, with reciprocal withdrawal of overflight rights already in effect.

The conflict could cost India billions of dollars. Even after a ceasefire, rebuilding infrastructure and replenishing armaments would strain public finances. Both currencies would likely weaken due to capital flight and lower export earnings. The Pakistani rupee, with its fragile reserves, is especially vulnerable.

Should the confrontation extend, the macroeconomic fallout could intensify—fuel and food inflation, war insurance surcharges, and tightening of credit could compound stress, especially in informal and consumption-led segments of the economy.

Sectoral impacts could be uneven but notable. Tourism, already fragile in India and minimal in Pakistan, would likely see a sharp decline. Trade with third countries might be affected as supply chains adjust to uncertainty. Remittances and labour-related exchanges, such as medical tourism and trucking, could face disruptions. Energy imports may become more expensive due to increased insurance costs and perceived route risks. Some multinational firms might adopt a wait-and-watch approach, delaying expansion or capital deployment until clarity returns.

While the present exchange of fire may not spiral into full-scale war, even a short kinetic episode could carry long economic and reputational shadows. A prolonged conflict would set both nations back by several years—economically, diplomatically, and in terms of regional influence.