.png)

When IPO Red Flags are Allowed Marketing Spin

Belrise Industries IPO reveals the poor evaluation standards applied by regulators, underwriters, and institutional investors.

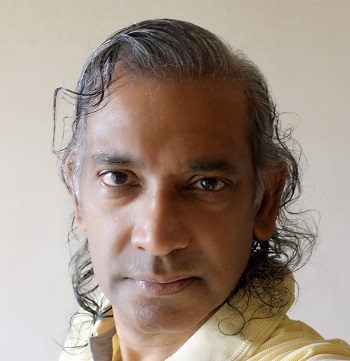

Dev Chandrasekhar advises corporates on big picture narratives relating to strategy, markets, and policy.

July 11, 2025 at 2:18 AM IST

In the frenzied world of Indian IPOs, few things capture investor imagination quite like a "foreign broker endorsement."

On July 7, Jefferies initiated coverage on Belrise Industries with a buy rating and 31% price-rise target. After trading in the ₹100-₹103 channel for weeks following its May 28 listing, Belrise shares surged 9.40% to ₹112 on July 8, the day after Jefferies published its research report.

It's also less than a couple of months after Belrise's ₹2.14 billion IPO of which Jefferies was a co-manager and key underwriter.

Coincidence perhaps, because the Securities and Exchange Board of India has rules for research independence, including mandatory cooling-off periods between underwriting and research coverage. Investment banks typically must wait 30-40 days before initiating coverage on companies they helped list, ostensibly to prevent conflicts of interest and ensure analytical objectivity. Jefferies appears to have played by the rules, waiting roughly two months after Belrise's listing before launching coverage.

But technical compliance with cooling-off periods misses the larger, more niggling question is how did a company with such glaring structural flaws secure regulatory approval and investor backing in the first place?

IPO Games

Beneath the marketing gloss, Belrise is essentially a one-trick pony masquerading as a diversified growth story. It remains dependent on Bajaj Auto as its primary customer, a concentration risk that transforms any investment thesis into a leveraged bet on a single client's fortunes. This fundamental vulnerability, along with other red flags, was meticulously documented in Belrise's Draft Red Herring Prospectus.

The question isn't whether these risks were disclosed; it's how they slipped past regulators and investors despite hiding in plain sight. The answer reveals systemic failures that extend far beyond individual bank conflicts to the heart of India's IPO ecosystem. Here, disclosure becomes a substitute for evaluation, and regulatory approval becomes a stamp of legitimacy rather than quality assessment.

The answer lies partly in the sophisticated ecosystem that has emerged around IPO marketing. High-frequency trading firms like Graviton Research Capital, HRTI Private Limited, and OM Trading have played crucial roles in amplifying trading volumes and drawing attention to the stock. These algorithmic traders don't necessarily care about fundamental value—they're part of the nexus involving momentum signals, news flow, and volume patterns that can create the illusion of organic investor interest.

The post-Jefferies surge wasn't coincidental market appreciation; it was a coordinated response to perceived endorsement from a "credible" foreign institution. Retail investors increasingly take positions based on this manufactured momentum rather than fundamental analysis.

Troubling Questions

Strip away the promotional veneer, and Belrise presents a case study in everything sophisticated investors should avoid. The company conducts 26% of its sales and 29% of its purchases through related-party transactions. Such self-dealing should trigger immediate scepticism in any mature market. The company's Byzantine web of affiliated entity dealings makes it impossible to assess whether reported margins reflect genuine operational efficiency or transfer pricing manipulation.

The recent ₹1.9 billion acquisition of H-One India exemplifies the execution risk that should have concerned deal managers. The target operates at "relatively low capacity utilisation," yet projections assume dramatic efficiency improvements. Such kind of heroic assumptions suggest either analytical incompetence or deliberate optimism.

Jefferies projects 12% annual growth in a market expanding just 10-11%, implying systematic market share gains despite Belrise already commanding 24% of key segments. The firm's optimistic scenario relies heavily on financial engineering—specifically, debt reduction from IPO proceeds—rather than operational improvements. When analysts project 18% earnings growth based primarily on spreadsheet projects rather than business fundamentals, it suggests the research process has been compromised from inception.

Belrise trades at 0.8 times its price-to-earnings-growth ratio versus 1.8 times for peers, but this comparison ignores fundamental quality differences. Companies with transparent operations, diversified customer bases, and clean corporate structures rightfully command premium multiples.. Analysts that ignore these quality distinctions are essentially arguing wrongly that auto-component businesses are interchangeable.

How did underwriters justify bringing a company with such concentrated customer exposure to public markets? The investment banking standards applied to Belrise's IPO raise troubling questions about the analytical rigor applied to listing decisions.

The timing of the IPO itself raises additional questions. Why did controlling shareholders choose to access public markets now rather than wait for the two-wheeler industry to fully recover? The answer may lie in the very dependencies that make Belrise vulnerable. When your business model relies on a single customer in a cyclical industry, market windows become precious and fleeting.

Systemic Implications

When companies with glaring vulnerabilities can successfully access public markets and receive positive research coverage, it teaches the wrong lessons about investment analysis. Retail investors begin to believe that regulatory approval substitutes for fundamental analysis, that disclosure documents are irrelevant if the story sounds compelling, and that professional research coverage validates investment theses regardless of underlying quality.

Regulators need to assess whether disclosed risks make companies unsuitable for public investment, not merely whether risks are properly disclosed. Investment banks need to apply consistent analytical standards regardless of commercial relationships.

Retail investors often view regulatory approval as validation of investment merit rather than merely disclosure compliance. When SEBI approves an IPO, many assume the underlying business has passed some quality threshold beyond basic legal requirements.

The sophisticated money should have known better. Institutional investors presumably have the resources to conduct proper analysis and identify structural vulnerabilities. Their participation suggests either analytical failure or a bet that retail enthusiasm would provide exit opportunities regardless of fundamental merit.

The real test will come when market enthusiasm fades and fundamental realities reassert themselves. By then, the sophisticated money will have moved on, leaving retail investors to discover that proper disclosure and regulatory approval don't necessarily translate to investment merit. The cooling-off periods may have been observed, but the underlying conflicts of interest between deal flow and analytical integrity remain as potent as ever.