.png)

Vivek Kumar, an economist at QuantEco Research, focuses on the Indian economy and specialises in the macro-quantitative intersections in the currency and bond markets.

August 5, 2025 at 5:16 AM IST

US President Donald Trump carries a reputation for being an aggressive dealmaker with an eye for quick wins. Among other things, his book with Tony Schwartz, ‘The Art of the Deal’, talks about leveraging strength and media attention in negotiation tactics, while maintaining multiple possibilities and being adaptable to changing circumstances.

Trump has displayed most of these, while staying his ground on his publicised reset in the US tariff structure despite the unambiguous lack of academic and empirical evidence with respect to such a populist move.

India saw a marginal reduction in its tariff from the 26% “Liberation Day” announcement on April 1 to 25% as applicable from August 1. The revised tariff schedule has put India on a backfoot, relatively speaking:

- The average tariff for the top 50 countries/regions in the world, excluding China and Russia, has moderated from 17.9% from April 1 to 15.9% in the August 1 announcement. India’s distance from the mean has increased instead of converging.

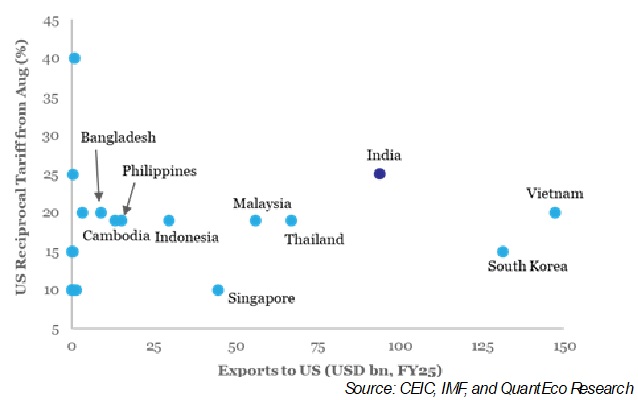

- Within EM Asia, excluding China, the tariff ranges between the baseline rate of 10% on the lower side to as high as 40%, with a weighted average rate, by respective exports to the US in 2024-25, of 17.5%. India in particular stands at a disadvantageous position—its tariff of 25% is the second highest in EM Asia along with Brunei, especially compared to countries like Singapore, South Korea, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. Notably, for reasons unknown, some of the countries saw drastic reduction in their respective levels of reciprocal tariff just a day before President Trump’s announcement on July 31. It is being speculated that some of these countries in order to dodge the high tariff bullet have agreed to grant generous concessions to the US with respect to either lower tariff and non-tariff barriers, greater market access, and investment commitments. Lack of specifics in the ambiguous official communication from involved countries, including the US, is rather conspicuous.

Assessing the economic impact of the reset in the US tariff structure is a complicated task because of the fluidity of the situation and ambiguous communication. Nevertheless, one could analyse the impact through a broad macro lens by estimating the gross standalone impact, the net cumulative impact, and the generalised global spillover impact.

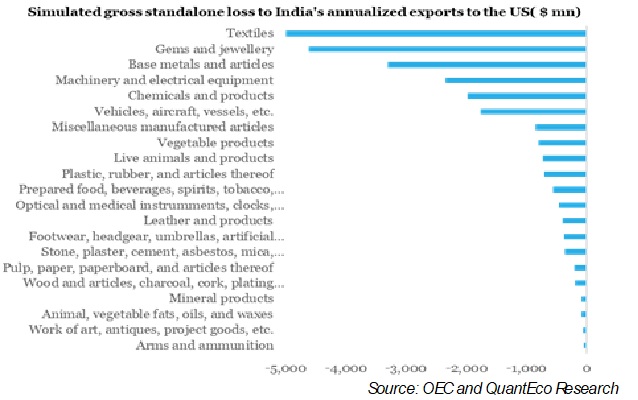

We utilise the Observatory of Economic Complexity’s data visualisation platform to assess the gross standalone impact of the US reciprocal tariff on individual countries. Few observations:

• On a gross standalone basis, India could potentially see an annualised reduction in its exports to the US by about $31 billion.

However, India also stands to gain potential export market share of about $29 billion on account of tariffs imposed on other countries.

- As such, on a net cumulative basis, India could potentially lose $2 billion worth of annualised exports to the US.

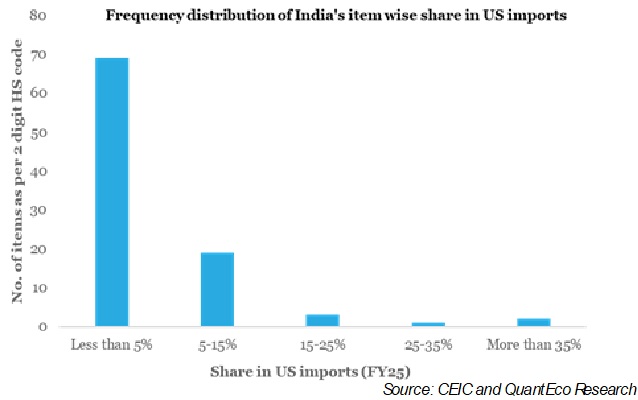

- The net loss in exports could be insignificant where US has a major dependence on India as supplier. Out of the 98 categories of goods as per the 2-digit HS Code classification:

- There are five items where India’s share in US imports is 15-40%. The US imported $5 billion worth of these items in 2024-25. It is unlikely for the US to find alternate exporters for such items due to their unique value.

- In addition, there are 19 items where India’s share in US imports was moderately high at 5-15%. The US imported $26 billion worth of these items in 2024-25. Finding alternate suppliers could be possible for such items, but it could be a drawn-out process.

- While the net loss for India appears small—$2 billion amounts to 0.05% of India’s 2024-25 GDP—there could be a non-negligible adverse sectoral impact. For instance, labour intensive sectors like textiles gems and jewellery, machinery and electrical equipment, chemicals, auto components, etc. could face a higher degree of hardship compared to others.

- Although the US is the largest export destination for India, its share in India’s GDP stood at 2.2% in 2024, this is significantly lower compared to 29.7% in Vietnam, 27.3% in Mexico, 18.4% in Canada, 14.9% in Taiwan, 12.5% in Malaysia and 12.0% in Thailand. A US-led moderation in demand conditions would have a significant adverse impact on manufacturing and investments decisions in the highly exposed countries. The overall cascading impact could lower the World GDP growth. The IMF estimates World GDP to decelerate by 30 bps and 20 bps in 2025 and 2026, respectively versus 2024. This could drag India’s 2025-26 GDP growth by 10 bps.

Beyond the impact on GDP growth, one could expect the following macro trajectories to evolve over the next 1-3 years:

- A higher inflation in the US accompanied by a deflationary impulse in rest of the world. Countries like China with excess manufacturing capacity could be leading this trend.

- A moderation in US trade deficit would lead to an adjustment in the rest of the world’s trade surplus. In effect, trade surplus economies could see a lower surplus while trade deficit economies could see a wider deficit. The net impact would, however, be nuanced depending on how individual countries are impacted.

- There could a pressure on fiscal deficit globally, with governments feeling the need to provide a safety net for sectors bearing the maximum brunt of the tariff adjustment.

- Capital flows could align with the new world order marked by significant weakening of multilateralism. This might create instability in the interim period resulting in financial market volatility. Policymakers to create safeguards with various forms of financial market intervention in their respective countries, while exploring avenues to attract durable capital through structural reforms.

- From RBI’s perspective, these developments would determine its policy reaction function for the Indian economy. At a broader level, policy ideation could be centred around some of these aspects:

- If the US tariff-led reset in global trade results in a permanent reduction in the global growth momentum, then how would this impact the Indian economy on a structural basis?

- Would this lead to a reassessment of the ‘neutral policy rate’, especially if core inflation pressures remain benign amidst a global deflationary backdrop?

- What should be the FX policy in such a scenario? With greater uncertainty now becoming embedded in the macroeconomic discourse, would conventional metrics of external vulnerability and reserve adequacy warrant finetuning?

Focusing on the near term, the relatively higher tariff on India leaves one with frayed nerves. After all, trade negotiations were continuing at a frenetic pace, notwithstanding the impractical timeframe of few months for something that normally takes years to accomplish.

Diplomatic protocol and adroitness offer little manoeuvrability at this stage for India to immediately diffuse the fallout from Trump’s headline grabbing announcement. It is best to introduce a cooling phase for now and get back to the negotiation table by striking a balance between India’s need for trade reforms and its economic and political sensitivities with respect to the employment-heavy sectors, especially agriculture and the MSME.

While it is not clear how much additional time it would take to iron out frictions, a lot can still be agreed upon mutually in order to frame a preliminary version of the India-US Bilateral Trade Agreement. India could look to sweeten the deal by slashing tariffs on low-volume items, especially the ones often highlighted by President Trump while committing to increase defence and energy procurement from the US. The 25% tariff on India could very well turn out to be an ‘interim tariff’, which eventually gets revised lower in the coming months.

For the US, one hopes that President Trump and his trade team do not miss the woods by remaining obsessed about the trees!