.png)

Phynix and Starsailor travel with different compasses. Phynix chases flavour and a pause from the grind. Starsailor, a music industry veteran, travels for gigs, vibes, vinyls, snooker, and lasting friendships.

May 25, 2025 at 5:07 AM IST

一期一会 or Ichi-go ichi-e. Each meeting is a singular, irreplaceable moment. The night that lives on, somewhere between the photographs, the sake, and the silence.

The Door Without a Name

Kyoto is a city of secrets. It folds its stories into alleyways, tucks them behind sliding wooden screens, and hides them in plain sight beneath the neon hum of Gion’s lights. But this secret was wedged inside a nameless black door in an unremarkable building.

We weren’t looking for magic. We were looking for food on a cold, rainy night.

We had taken an elevator to the fifth floor to a jazz bar, only to find a largely dull spot, a crackling record player, and a bowl of edamame that mocked our hunger. Desperate, we descended into the belly of the building, and soon found ourselves in front of a black, unmarked door on the third floor.

I’ve since wondered: What compels humans to knock on doors with no signs? Maybe it’s the same instinct that makes us peek into our Christmas gifts before we are supposed to, or go down the rabbit hole while researching a conspiracy theory at 2 a.m. Curiosity, that glitch in our survival programming.

We knocked.

The Time Capsule

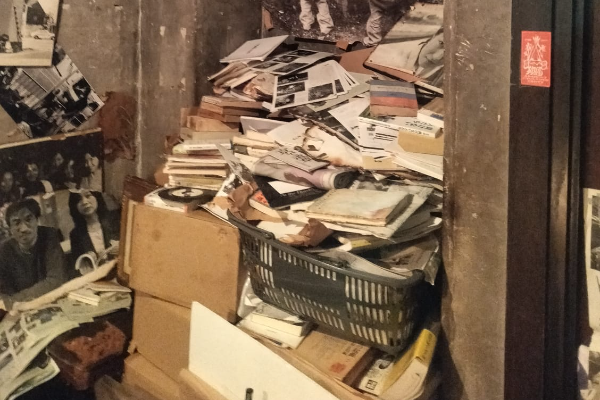

The door creaked open to a scene that felt less like a bar and more like a sketch by a tipsy Hayao Miyazaki. Imagine a room where clutter seems to have achieved sentience: shelves sagging under photo books and walls plastered with black-and-white ghosts of 1970s Kyoto.

The dive bar looked so disorderly that it felt like a universe at its highest entropy, as if everything had the freedom to be where and how it wanted to exist, uncontrolled. The air smelled of sake, dust, and the faintest whiff of history. The lighting? Bad in a perfect way.

Three faces swiveled toward us. An elderly man behind the bar (Kai Fusayoshi, though we didn’t know it yet), a woman in a white turtleneck (Sofie, who turned translator for a few hours), and a middle-aged man in a vibrant pink-grey shirt and a pink dotted tie (Shinji Ishii, novelist, music enthusiast, and accidental DJ).

No tables. No menu. Minimal English. Just a chorus of “Hai! Hai!” and Shinji leaping up to offer his stool. Kai-san himself emerged from behind the counter and offered us warm sake. “No food,” he said, “beer, sake? yes.” Despite our hunger, something told us to stay.

We sat, not yet realising we’d stumbled into a living collage of Kyoto’s counterculture—a bar owned by a photographer-activist who had spent decades turning rebellion into art, a love letter to humanity.

The Man Who Shot Kyoto’s Soul

Kai Fusayoshi is the kind of person who wears his life like a well-loved leather jacket: frayed at the edges, studded with stories, and impossible to replicate. Kai instantly reminded us of the Philippines’ Effren ‘Bata” Reyes (the greatest player the game of Pool was ever graced with). Languid, easy shoulders and a kind, mischievous smile. The burden of a genius.

Born in 1949 in Oita City, Kai’s journey began when his sister handed him a camera to stop him from shooting chickens with an air rifle. That gift turned into a lifetime of capturing lives, mostly in Kyoto.

In 1972, at the height of the student protest movement, Kai opened Honyarado, a café that quickly became a haven for misfits: anti-war activists, folk singers, poets, and lost lovers. He photographed them all.

In 1985, he opened this bar—Hachimonjiya—and started photographing his customers: portraits of beautiful women, candid shots of Kyoto locals, children by the river, artists, strangers. It was quieter than Honyarado; slower, more distilled. The clientele changed, but Kai stayed the same. His camera told Kyoto’s story better than any textbook ever could. He took our pictures too. Of course he did.

Kai runs the bar, but to put it more aptly, the bar is him. Hachimonjiya is a capsule of Kai’s memory, style, and rebellion—a shrine to timeless beauty and wry resistance. Thanks to our language limitations, he made no small talk. But give him a spark—a shared memory, a wobbly Japanese phrase—and he’s off, rummaging under the bar to show you one of the many photo books.

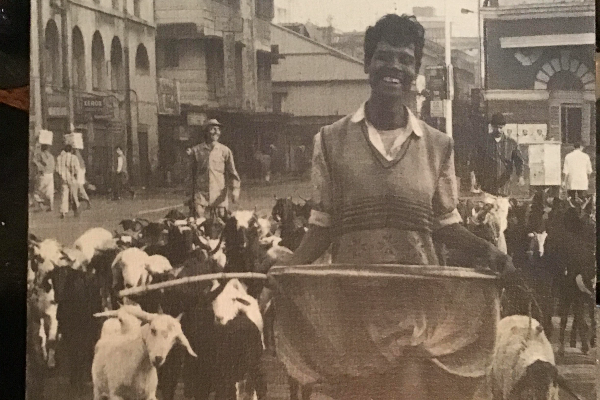

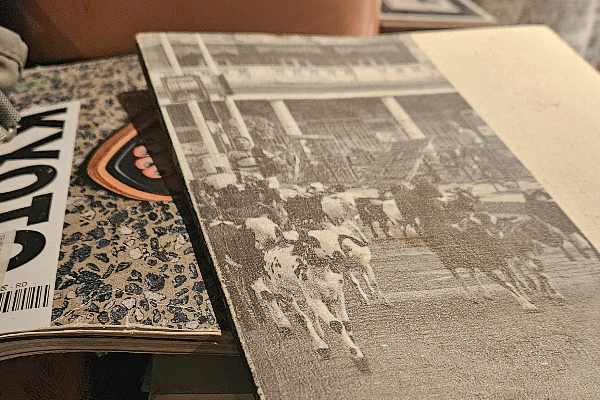

As he learnt about our origin, Kai intently started looking for something. Moments, and a few staccato conversations later, he emerged with a photo book titled India Straight, shot in 1997-98. Its cover: a smiling goat herder cutting through a busy street with his flock like a man untethered from time. The traffic swirls, heads turn, but he keeps walking, barefoot and beaming. The book was full of life, of an India many of us miss—grainy docks of Kochi, sun-baked faces in Kolkata, women wrapped in soft cotton in busy markets, and weathered fishermen casting nets.

The Novelist

Enter Shinji Ishii, the man sporting the pink tie. His only English-translated work, Kutze, Stepp’n on Wheat, follows Cat—a character growing up in a surreal port town with a grandfather and a father chasing an unsolved math proof. Haunted by a phantom dancer, Cat dreams of following him across the sea.

The Osaka-born novelist says he could never leave Kyoto—the calm suits him, a balm after the 'loudness' of his hometown. And yet, he dreams of visiting a place as wild and chaotic as Mumbai. All night, he doesn’t stray from his role as DJ, not even when the bar empties, and we’re the last ones left, letting the memory soak into our bones.

He dropped the needle on scratchy records featuring songs by Mohammad Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Suman Kalyanpur and Lata Mangeshkar. There is nothing stranger, or more sublime, than hearing “Dekho Ab To Kisko Nahin Hai Khabar” in a Kyoto dive bar. Shinji grinned. “India! Beautiful country, beautiful music!”

A bar stool away, Tate—an LA artist whose house had burned down just weeks earlier—nodded along. Despite everything, she came anyway because she couldn't afford to cancel. “I came because… well, everything was planned and booked,” she shrugged. Behind her, on the couch, two Austrians drank beer, silently absorbing a night that defied translation. Meanwhile, somehow sensing the energy, the background music changed to Dire Straits’ eponymous debut album.

Books lay open like quiet conversations on every table. A city of strangers had become a room of kindreds.

The Art of Holding On

What alchemy turns strangers into co-conspirators? Maybe it’s the sake. Or the way Shinji’s vinyl scratches seemed to sync with the quiet drizzle outside. Or Kai’s photos, whispering from the walls.

We talked until the streetlights blinked off, hunger all but forgotten. Kai showed us portraits of his subjects spanning decades, each face a novel unto itself.

As we left, Kai insisted we take a copy of the photo book, but we couldn’t. It almost felt wrong to take it out of the shrine. And what if he couldn’t find another copy for the next visitors from India? We couldn’t bear to deprive them of it.

Walking back through Gion, I thought about fire. How it ravages, yes, but also reveals. Kai’s surviving photos—10% of a lifetime’s work—gleam brighter for their scarcity. They’re proof that beauty isn’t in the volume of what we keep, but the voltage of what we share.

There’s another phrase in Japanese: natsukashii—a kind of sweet, aching nostalgia. It doesn’t just mean “I miss that.” It means “That still lives in me.”

Hachimonjiya is natsukashii made real. A place where the past is not preserved, but fermented—growing richer and stranger with each passing year. Where photographs aren’t artifacts, but conversations. Where Kai still stands behind the bar, sizing you up for your moment in his lens.