.png)

Gurumurthy, ex-central banker and a Wharton alum, managed the rupee and forex reserves, government debt and played a key role in drafting India's Financial Stability Reports.

May 20, 2025 at 3:37 AM IST

The Reserve Bank of India published an article titled “Three Years of Standing Deposit Facility: Some Insights” in its April Bulletin.

The article stated:

“In the Indian context, the Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) was first recommended in the report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (Chairman: Dr. Urjit R. Patel, 2014) as part of the overhaul of the operating framework of monetary policy.”

The amendment to Section 17 of the RBI Act in 2018 enabled the Reserve Bank to institutionalise the SDF. It was eventually introduced in April 2022, replacing the Fixed Rate Reverse Repo as the floor of the Liquidity Adjustment Facility corridor.

While the Urjit Patel Committee is widely credited with formally recommending the SDF, the underlying concept had been considered much earlier. The RBI’s recurring challenges in managing excess liquidity, whether from large capital inflows or one-off events such as demonetisation, had already exposed the limitations of relying solely on collateralised tools. It is therefore inaccurate to view the idea as originating solely with the Patel Committee.

One key obstacle to earlier implementation was the absence of an enabling legal framework, which was only addressed in 2018.

But this raises another question: why did it take four more years after the legal amendment to operationalise the SDF? Perhaps the reason is simply the absence of a compelling, immediate need at the time.

In this context, Governor Sanjay Malhotra’s recent reminder to banks to engage more actively in the call money market, rather than relying heavily on the SDF, becomes highly relevant.

The Bulletin article further notes that the “simultaneous occurrence of liquidity deficit conditions alongside substantial fund placements under the SDF suggests asymmetric distribution of liquidity within the banking system and the increased liquidity preference of banks.” This reflects a growing precautionary motive among banks amid a 24/7/365 payment ecosystem and more efficient government transactions, which have reduced the float available with banks.

Notably, it was by deliberate policy design that market participants were nudged away from the uncollateralised call money market toward collateralised transactions. This rationale of this shift was well-articulated in policy documents: reducing systemic risk and borrowing costs.

Meanwhile, one development that hasn’t received widespread attention is the introduction of ASISO, or the Automated Sweep-In and Sweep-Out mechanism, by the RBI. This feature allows banks to automatically place excess funds with the SDF or draw liquidity via the Marginal Standing Facility when pre-set thresholds are reached.

It’s a smart tool — to borrow a Trumpism, a “beautiful thing.”

A technical glitch that occurred a year ago, disrupting crucial money market data dissemination due to a malfunction in this very system, has suddenly but briefly raised awareness of ASISO’s existence, beyond its users.

That said, curiously, the fixed reverse repo rate remains at 3.35%, a full 240 basis points below the SDF, a rather surprising spread.

What role does variable rate repo/reverse repo play, specifically for tenors where there's an LAF instrument available? A reverse repo rate that is unresponsive to the prevailing liquidity regime, yet is used to absorb liquidity, defies logic.

While the RBI’s operations still retain the character of a “corridor,” the question arises: could the system drift towards a “floor” regime, driven by persistently high SDF rates, if supported by a high liquidity buffer?

A look at a US experience may be instructive.

The Corridor

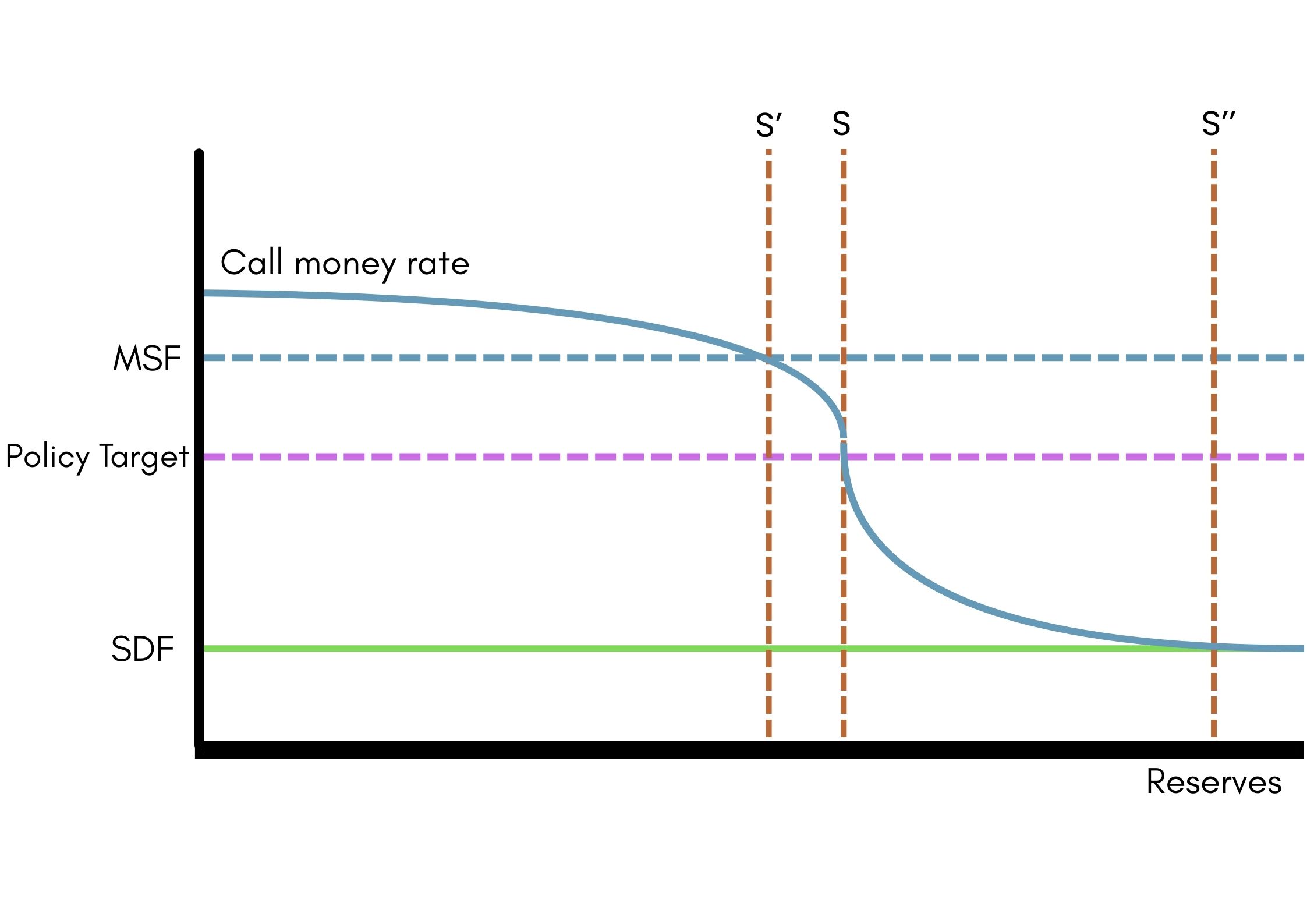

The dynamics of liquidity and policy rates are evident in the diagram below:

When RBI provides liquidity just sufficient to meet systemic needs, the target rate aligns closely with the policy rate (supply denoted as S). In such scenarios, banks tend to transact among themselves, redistributing reserves internally.

When RBI provides liquidity just sufficient to meet systemic needs, the target rate aligns closely with the policy rate (supply denoted as S). In such scenarios, banks tend to transact among themselves, redistributing reserves internally.- When liquidity is insufficient, the target rate moves upward, with the MSF acting as the ceiling — since banks with shortfalls may have to borrow from the RBI.

- Conversely, when liquidity is excessive, the rate drifts down to the SDF floor (supply denoted as S”).

Now, consider what happened in the US in early 2019.

On January 30, the Federal Open Market Committee officially decided to adopt a floor system, moving away from a corridor approach. Many argue that, since the Global Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve had already been operating a de facto floor system.

The rationale for this shift was to maintain a sizable buffer above the structural demand for reserve balances, reducing the Fed’s need to finely manage liquidity.

However, this decision, which surprised markets, invited criticism. Critics argued that the new system was inherently unstable. Behavioural shifts in banks, accustomed to the excess reserves, could make it difficult for the Fed to scale back liquidity sharply, if need be, without disrupting the system, leading to an insatiable appetite for central bank accommodation.

In other words, the Fed risked entanglement in a financial ecosystem increasingly reliant on its balance sheet. Critics also noted that the Fed’s attractive Interest on Reserve Balances encouraged this dependency and constrained its ability to shrink its balance sheet, while in a way also kept interest rates high.

A similar concern was expressed by Norges Bank in 2010, when it decided to shift from an abundant to a scarcer reserves regime:

“When Norges Bank keeps reserves relatively high for a period, it appears that banks gradually adjust to this level… With ever increasing reserves in the banking system, there is a risk that Norges Bank assumes functions that should be left to the market. It is not Norges Bank’s role to provide funding for banks… If a bank has a deficit of reserves towards the end of the day, banks must be able to deal with this by trading in the interbank market.” (Norges Bank 2010)

In many ways, India’s SDF functions like the Fed’s Interest on Reserve Balances, but with two key differences. First, unlike India, the US does not mandate minimum reserves for banks. Second, the SDF explicitly remunerates banks for surplus balances, effectively serving as a policy tool for absorbing liquidity.

This perhaps explains Governor Malhotra’s concerns that banks, emboldened by the comfort of SDF and ASISO, are engaging with the RBI, rather than with one another, when it was intended to be the depository of last resort.

In any case, when CCIL data on a typical day shows that TREPs and repos together account for around 95% of overnight transactions, while the call money market plays a minimal role, often clearing below the corridor, the phrase “slide toward the floor” is no longer just a figure of speech. One hopes the market timing changes recently proposed by an internal RBI committee will offer some remedy!!

Part 1 explored how the LAF matured from a daily liquidity tool to the operational heart of monetary policy. Part 3 will examine whether the call money rate, once central to policy signalling, still deserves its place in the corridor.