.png)

By Srinath Sridharan

Dr. Srinath Sridharan is a Corporate Advisor & Independent Director on Corporate Boards. He is the author of ‘Family and Dhanda’.

September 20, 2025 at 7:40 AM IST

This is not a commentary on religion. It is a critique of the easy rhetoric by which wealth, enterprise and ambition are being cast as sins at precisely the moment when societies not only need kindness, but also wealth and job creators.

The Catholic Church has never been ascetic in its material pursuits. Its great cathedrals, artworks and institutions were built on the foundation of tithes and donations, making it both a spiritual and temporal power. Wealth has long been both its sustenance and its armour. Against this backdrop, the Pope’s censure of entrepreneurs who accumulate riches through innovation and risk carries the uneasy ring of selective morality.

The warning against fortunes built on enterprise risks erasing the long history of the Church’s own reliance on wealth, privilege and hierarchy. For centuries it has been one of the most enduring repositories of capital in human history. Its treasures and landholdings were not funded by modest living, but by contributions from generations of the faithful. To now censure wealth creation through innovation has the quality of historical amnesia.

The irony is sharper still when one recalls the sale of indulgences, whereby the faithful were asked to pay for the remission of sins. That practice was not only theology but also finance, funding grandeur even as it stirred resentment among those who saw salvation being monetised. The Reformation itself was triggered in part by this uneasy marriage of money and morality.

Nor is this only a medieval memory. In more recent times, questions have been raised about financial management within Church institutions, underlining the difficulty of reconciling moral authority with material stewardship. These are not isolated lapses but part of a continuum in which institutional wealth and moral guidance have sometimes sat uneasily side by side.

If the Church were itself a corporation, its record on transparency and governance might attract scrutiny of the kind regulators apply to businesses. It is precisely because it cloaks itself in moral sanctity that it often escapes such interrogation. Yet when it presumes to lecture those who generate wealth through enterprise, risk and innovation, the result is less moral clarity than moral selectivity.

History makes plain that fortunes amassed by the Church did not always uplift society. They often entrenched hierarchy and privilege. By contrast, modern entrepreneurship, however imperfect, creates products, technologies and industries that transform lives. To portray the one as virtue and the other as vice is to invert the lessons of history.

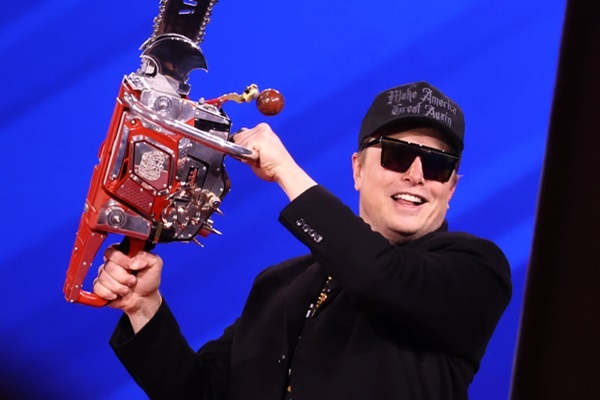

Elon Musk’s prospective trillion-dollar pay package at Tesla is not manna from heaven. It is a wager by shareholders that impossibly high incentives can extract impossibly high performance. This is the logic of capitalism: wealth is created, not redistributed by decree. Musk’s rewards are not siphoned off the payslips of Tesla’s workers. They are contingent on value that does not yet exist, value that will only emerge if his vision materialises.

This also places a responsibility on companies to be fair in the wages they pay across the board. The oft-cited median pay ratios may have relevance in mature industries with predictable risks and stable models. Yet in new-age sectors defined by unknown unknowns, the calculus shifts. To promote leaders to pursue audacious goals, monetary incentives remain one of the few instruments that reliably work, even if they produce headline figures that unsettle the moralists.

The Pope’s remarks are not isolated. They echo a rising chorus of voices across multilateral forums and activist circles that cast extreme wealth as a social ill in itself. Whether in calls for global wealth taxes, demands for ESG compliance to be stretched into redistribution, or the rhetoric of stakeholder capitalism, the mood of our times is to conflate reward with inequity. Yet history shows that punishing scale in achievement rarely uplifts the poor. It merely flattens the incentive to attempt the extraordinary.

There is also a principle of legitimacy at play. Tesla’s board, backed by shareholders, explicitly tied Musk’s fortunes to targets they considered virtually unattainable. The contract is not a papal indulgence. It is a bargain struck in a marketplace of risk and expectation. When critics moralise about such arrangements, they overlook that this pay package is not imposed upon society. It is a voluntary compact of risk and reward.

The easy comparison of CEO pay with worker wages, repeated like a moral incantation, misses the point. The modern chief executive is not merely a custodian of payrolls. At the frontier, they are architects of technology, capital and talent on a global scale. To equate such responsibility with multiples of a worker’s wage is arithmetic without analysis.

History shows that progress is fuelled not by envy but by ambition. Wealth concentrated in the hands of builders has financed voyages across oceans, industrial revolutions, space exploration and digital networks.

Religion and morality have always been intertwined, shaping codes of conduct and collective values. Yet morality untethered from economic reality can be as destructive as greed. Societies that vilified enterprise in the name of virtue often stagnated. The medieval injunctions against usury, for instance, were meant to protect the poor from exploitation, yet they also throttled credit and commerce until new financial innovations emerged in Renaissance Italy. Prosperity returned not when profit was denounced, but when rules were crafted to channel it productively.

Human history is replete with examples of wealth powering social progress when it was proportionately shared and responsibly governed. The flourishing of cities like Amsterdam in the seventeenth century or Manchester in the nineteenth was not built by monks’ austerity but by merchants, innovators and industrialists. Where states ensured that prosperity spilled beyond guild halls and stock exchanges, they created robust middle classes, civic institutions and eventually political freedoms. Where elites hoarded without care for those excluded, as in ancien régime France, the result was not stability but revolution.

India too offers living evidence of this balance between ambition and responsibility. The IT services boom created not only millionaires in Bengaluru but also millions of middle-class jobs that lifted families into education, housing and healthcare. The pharmaceuticals industry has delivered affordable medicines worldwide while building world-scale firms at home. The rapid rise of digital payments has enriched founders and investors, yet it has also given street vendors and small merchants access to formal financial systems for the first time. These cases show that when innovation and enterprise are enabled, prosperity can be both created and shared.

The lesson for nations is clear. The answer to inequality is not to beat down innovators or job creators, but to design systems where their success enlarges the circle of opportunity. History rewards societies that balance ambition with dignity, and punishes those that mistake resentment for justice. Economic growth and fair distribution are not enemies. They are twin imperatives, and only when pursued together do civilisations endure.

Societies that rush to criticise wealth creators and entrepreneurs who dare the impossible, must temper their jealousy with recognition of responsibility. The proper response is not to sneer at their success but to ensure that the systems in which they operate allow others a fair chance to rise.

Morality and the price attached to audacious leadership should not be confused. Those who dare to lead bear privileges as well as thorns, for the mantle of responsibility is never weightless. If simplicity and renunciation were the sole markers of virtue, leaders of faith would have lived in humble austerity, not in the vestments or monuments of grandeur that history has so often recorded.