.png)

Don’t Censor Content, Make Social Media Platforms Accountable

Bringing social media platforms under the same responsibility standards as traditional media can curb harm without curbing speech.

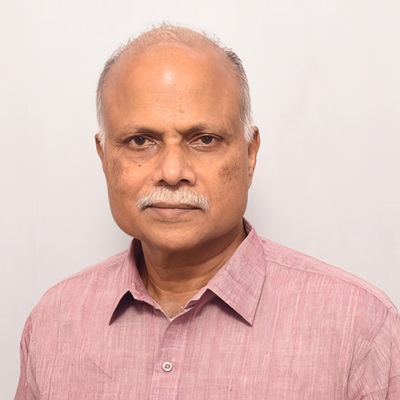

T.K. Arun, ex-Economic Times editor, is a columnist known for incisive analysis of economic and policy matters.

November 28, 2025 at 9:56 AM IST

The Supreme Court wants the government to set up an independent regulator for online content, while also asserting that it does not want to restrict free speech. Thinking of impossible things before or after breakfast generally has been considered to be the indulgence of queens in Wonderland. How royal privileges crumble!

The Court’s desire to check harmful social media content is entirely commendable. But instituting what effectively would become a censor board for social media is not the appropriate solution. Treating online social media platforms on par with traditional media in terms of being held accountable for the material they publish is the solution.

If a newspaper publishes a letter from a reader that is scurrilous, antinational, pornographic, libellous, defamatory or designed to cause enmity between people or communities, the publisher of the newspaper cannot shrug its shoulders and say, no staffer under the control of the publisher and its editorial leadership authored the impugned content. The publisher bears the full responsibility for what it permits to appear on its publication.

There is no reason to hold social media platforms to a different standard. When they carry on their platforms that shame or defame innocent people, and abet suicide, depression and stunted social and psychological development among the very young, they should not be allowed to use freedom of expression to defend their conduct.

Social media platforms cannot claim to be helpless in filtering out the undesirable. They do screen content for some things, child porn, and racism, for example. They employ algorithm to direct content to particular users to keep them glued to the site, feeding them what analysis of past consumption patterns tells them those readers find fascinating. Which means that they are not passive publishers of what users generate, but examine the content that users seek to publish.

The advent of powerful Artificial Intelligence reinforces the ability of social media platforms to filter out content that falls foul of norms devised by the platforms themselves in compliance with the laws of the land where they operate.

Social media platforms are used to the protection that Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act has accorded them, against being held responsible for the content that users generate and post on their platforms. The law also authorises them to remove obscene, excessively violent and other problematic content. Social media platforms have chosen to pick up the shield, but not the sword Section 230 offers them.

Since then, it has generally been taken as the norm that social media platforms are not accountable for user generated content, or UGC. It is time to move away from what has now become an archaic provision and is being opposed by the largest social media platform owner Meta itself.

Recently, Meta has joined legal battle with Ethan Zuckerman, a public policy professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who has sought the Court’s permission, under Section 230, the right to publish a piece of software that would allow any user to unfollow everyone on Facebook. Facebook contends that this amounts to an attack on the platform.

Such a piece of software was, indeed, published in 2020, by a British software developer, Lous Barclay, who found that he had a bonanza of free time after manually unfollowing everyone he used to follow on Facebook. He wanted to let everyone enjoy this gift of time by developing and publishing software that allowed anyone to unfollow Facebook contacts. Some 12,000 people tried out his software, reports New York Times.

But, in mid-July, Meta gave him legal notice to remove the software. He complied. This has inspired Prof Zuckerman to test Meta by demanding legal sanction for publishing software as UGC that would help Facebook addicts unfollow contacts and wean themselves of their addiction.

If Meta can block UGC that would harm its commercial interests by helping those on Facebook to unfollow people, why can’t it proactively block jilted lovers and blackmailers from posting revenge porn, stop bullies from tormenting pubescent boys and girls into self-harm and suicide or prevent its platform being used to mobilise armed cohorts to a pogrom?

Instituting a third party to scrutinise all content before publication effectively creates an official censor. That would certainly restrict freedom of expression, especially in these times of fragile egos that sense affront and demand retribution without restraint. If traditional media can go about its business without being pre-vetted by a censor, its conduct governed by the laws of the land, so can social media.

Social media companies have the technological expertise to devise and deploy algorithmic filters to hold publication of the small portion of UGC that is problematic and requires human vetting, while letting most content go public without delay. They can constantly revise and upgrade these algorithms. State-appointed censors would only gum up the process, at best, and trample free expression, at worst.

The solution is to bring social media on par with traditional media in terms of responsibility for what they publish. We don’t want no censorship.